Rebecca Brewer, Rochelle Goldberg, Charmian Johnson, Christina Mackie

Nature

January 26–March 3, 2018

Nature has its problems. Humans in particular treat nature as a cultural subject leading to the continual production of problematic clichés that ebb, flow and repeat through history. In times of political and cultural instability, the ideal of nature has become a conceptual and physical refuge from collective challenges, often with mixed results. While historically variable in its definition, nature has generally been understood in western culture as the material aspects of existence—but not the products of human activity. This distinction blurs quickly as the depth and breadth of human impact, interaction and interference into the natural world accelerates. It is this distinction that the artists in this exhibition contest, consider and trouble.

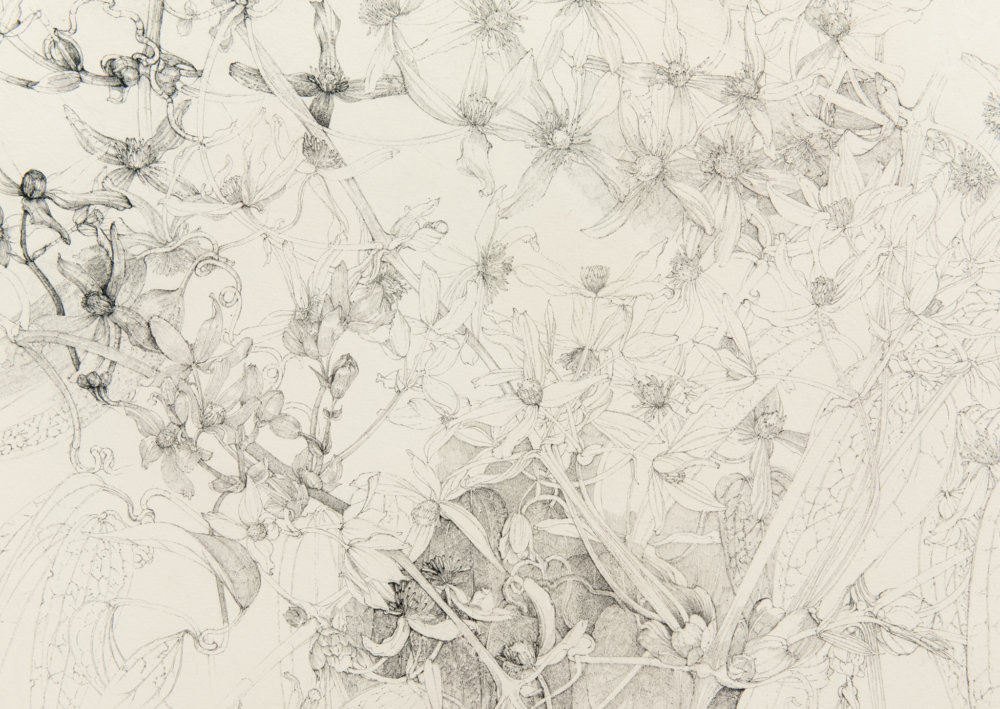

Charmian Johnson has been producing an evolving series of strange and incredibly refined ink drawings of flowers and plants for over 40 years. Taking cues from historical botanical drawings, the works of Albrecht Dürer and Aubrey Beardsley, and psychedelic graphics, Charmian painstakingly renders plant life of intense interest over months—even years. She does not work from photographs or other images, preferring observation and her own translational memory in rendering. A drawing of a single flower will contain information from all sides of itself, which she edits and composes as her own formal composition. Drawings from the ’70s made in Tangiers, Morocco are graphic, the plants’ outer forms and interior lines become integrated with abstract form and pattern. Work completed in Hawaii in the ’80s transition from bold lines to more detailed articulation, their tropical plant forms lending angles and edges. In works completed in her home of Vancouver, Charmian has developed compositions of increased subtlety and intricacy, each containing an abject anxiety of detail. In contrast to her attention to reality, she allows large areas of paper to be left empty—leaves, petals, stems and sketched areas of the work are left ‘unfinished’, and accidents and notes become aspects of the works’ composition. These renderings come up against suggested and self-imposed hard-edged borders on the page, only to transgress and push beyond them in another area, reflecting in microcosm the incredible history of the cultivation and breeding of flowers through subjective selection. In person, one is asked to move in closer to resolve the oddness of form, the immensity of detail, as much as nature asks of itself.

Christina Mackie’s Ambic asks for both a wide view of its form in space and contains details that also need a close physical encounter…just what is that? Two precisely fabricated wood tables are joined together, their width and length determined by the standard plywood sheets of their tops, suggesting a functional working surface. To what end, we are unsure. Atop this are seven large clear glass vessels—each custom blown, thick and unique, their openings face the surface of the tables’ skin, reminiscent of the alternative healing technique of cupping therapy. Not relying on suction to float material, the interior of four of these glass vessels contain onion skin and arbutus bark shavings suspended inside, supported by parafilm, a wax substrate used in both domestic canning and the laboratory to temporarily seal glassware; three others are empty, one with a wax film placed atop itself. The curved shape of glass here and the title of the work itself, allude to the history of the alembic—an alchemical still of two glass vessels connected by tapered tube for distilling chemicals. This reference to historical technology, combined with arbutus and onion skin, both natural materials used for dyeing material, speaks to colour as technological development, ancient tool, archaic device—the history of the creation of colour itself. ‘Ambic’ is also short for ammonium bicarbonate, a compound used in fixing dyes and pigments. The allusion to alembics, dyeing and sublimation is further articulated with the subtle placement of two glasses holding strips of paper seemingly stained by numerous colours, placed on the cross braces of the table as if ready to be brought up for use. The stains are the result of chromatography paper, which separates complex compounds such as paint into their distinct colour origins for observation. Ambic suggests the working process of connecting colour from one material to the substance of another material as a cultural production, despite its being a natural phenomenon. Colour as a force, force as deduced from observation.

Rebecca Brewer’s most recent wool felt collage is a twelve-foot high double-sided composition, similar in its hanging to heraldry or tapestry. Her textile works are developed concurrently with her painting practice, pursuing similar conceptual and formal experiments in differing material realities. One side of the felt presents a curved grid that is applied over top of multi-colored floating forms, suggesting a space beyond the wool lines, an interior that these forms occupy and one that we are looking into. The view is first presented with an overall impression of the grid, a repeating group of lines of equal consistency dominating our view, and it is only after coming to terms with it we can see underneath or through it. The other side of the felt offers another variety of coloured forms, this time applied over top of a grid pattern, suggesting the view from the interior, looking outward. On both sides, the grid is curved upwards, suggesting volume or perhaps gravity or weight pulling the centre downwards. On this ‘interior’ side, forms gather densely at the bottom of the composition, as a large fishing net weighted with marine life. The forms themselves, some more abstract than others, float in and out of legibility. What could be construed as fishing hooks are seen on both sides, or what may be pink coral is also coalescing lines, and it is the materials’ treatment and the accrued context of possible representational forms that suggest them. As with her paintings and previous felt works, Rebecca urges formal devices into suggested literal forms, in a symbolic or pictorial space that one can recognize, existing in a world of both representation and non-representation. With the grid or net, she asks us to consider its use in art history, as a human structure for systematically gathering natural life and structuring information, as well as continuing to use forms that blur between formal device, plant, animal or tool. The distinction between these blurs of abstraction, human and natural form—as in the world at large—remains elusive as the definitions and boundaries between human activities and what can be understood as the natural.

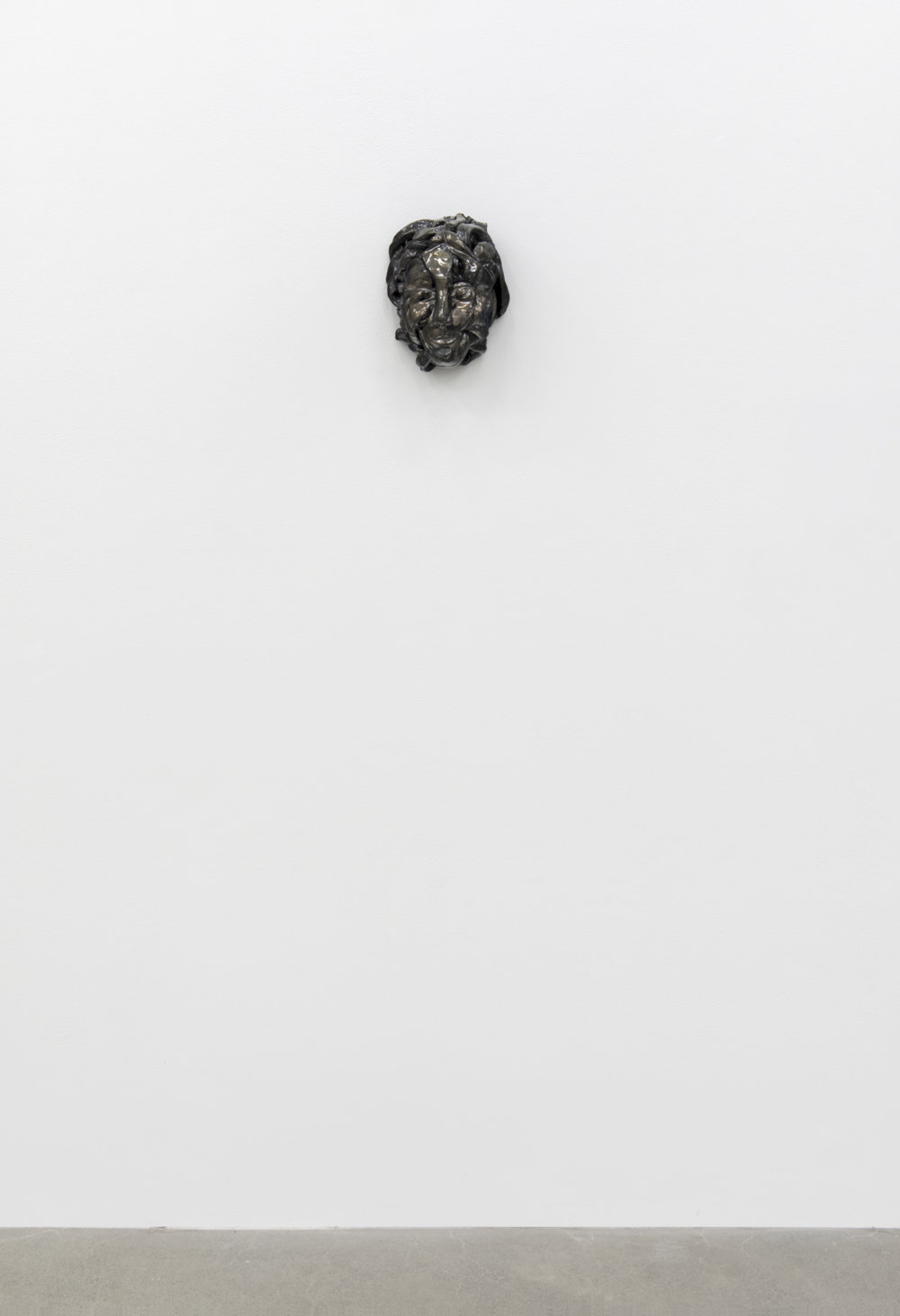

Rochelle Goldberg’s expansive sculpture and installation, Intralocutor: can you trigger the switch? expands her ongoing enquiries into the ebbing boundaries between entities, objects and humans–both the natural and the technological–the residue of encounter between material realities. For Intralocutor, she presents a carpet substrate as ground for numerous found, grown and fabricated objects, all in a similar gold chromatic blend. Chia seeds, a recurring material in her practice, were seeded, grown and expired for a three-month cycle on the carpets, both then sprayed with a mixture of shellac and gold paint, fixing the result of this cycle, the history of life and death now stable in synthetic fibres, deceased chia roots interwoven. Scattered on this carpet are dehydrated celery roots, exhumed for consumption, for a period still containing the power of growth as they would grow again if returned to the soil. Accompanying these are ‘light spills’, strands of LED lights embedded in pools of clear resin, powered by visible battery packs, and with these are brass casts of light switch plates placed on top, intentionally cast so thin that the material falls away in areas revealing the power source underneath. Beside this is a welded steel rod outline of a lampshade, its lowest edge woven with lights and its thin steel sprouting burnt matches cast in brass, appearing as brazed metal fungal growths. Together with this is a welded steel stand, anthropomorphic in scale, rather than holding the lamp shade as function would suggest, it supports a glazed ceramic bust of a figure, a floating human. Intralocutor: can you trigger the switch? digests cycles of organic growth and death, the production and consumption of power and the mechanisms of energy distribution, both fabricated and naturally occurring. These light/energy sources and systems, both historical (matches) and contemporary (LED, batteries, lamps, switches) further elucidate these cycles of consumption and expiration. Distinctions blur between human-made and naturally occurring entities, shimmering forward together.

Download Talking Points by Rochelle Goldberg.

Documentation by SITE Photography.