Eli Bornowsky, Jessica Stockholder

is a knot helpful

October 31–December 13, 2025

Eli Bornowsky and Christopher Mole in conversation

Wednesday, November 5, 6pm

Jessica Stockholder and Jesse Birch in conversation

Saturday, November 22, 2pm

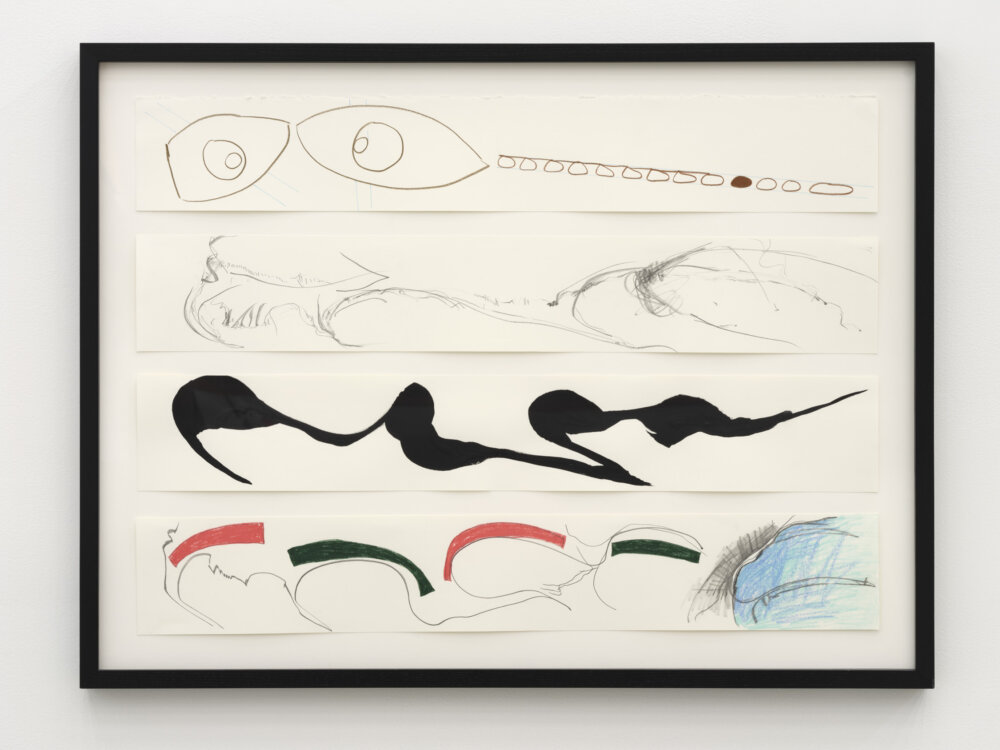

A knot is a line turned back on itself. A two-dimensional gesture becomes a spatial configuration, perhaps even unfolding temporally as we follow its arc from beginning to end. Whether formed by hand or through circumstance, a knot interrupts the flow to hold materials together through tension. Making use of lines, knots, and tangles, artworks by Jessica Stockholder and Eli Bornowsky draw connections across symbolic and material realities, tracing the entanglements through which perception takes shape.

Egg tempera paintings by Eli Bornowsky depict fragments of procedural tessellations. Cropped into square dimensions, the geometric compositions could extend infinitely beyond the picture plane. For the artist, whose practice often draws on optical effects derived from mathematical systems, geometric operations are a way to problematize artistic self-expression, engaging instead with the physical manifestations of algorithmic logic. For instance, Bornowsky employs ‘space-filling curves’ and ‘random walk algorithms’ to determine the distribution of colour across tiles. Both describe the wandering path of a line: one continuous and exhaustive, the other partial and unpredictable. Within these parameters, Bornowsky’s brush follows similar trajectories—looping, meandering, and doubling back—revealing the restless motion of his constructed process. By merging geometric precision with intuitive improvisation, his paintings explore the knot of structure and chance, where each brushstroke translates mathematic procedures into laboured rhythm.

For Stockholder, however, knots and lines serve as ways to cohere and compose dissimilar materials. One could imagine a random walk algorithm, more literally applied, carried out in the aisles of a hardware store or the heaps of a recycling depot. Because the daily experience of mass-produced goods is a sensation without sensitivity, Stockholder’s through-lines act as guides amidst the chaos of our post-industrial existence—a way to connect the dots across ambivalent constellations of meaning. Her compositions emphasize formal resemblances in order to contest taxonomies contrived through language, organized by function, or filtered by retail value. The result can be dizzying, as one is forced to reconcile bungee cords, rubber mats, and a travertine sink, as in Vanishing Point (2025) for example. Yet, Stockholder unifies such dissimilar surfaces with swaths of painted colour, inviting the viewer to consider each metonymic microcosm that signifies consumer desire, overseas labour, and the tangled logics that govern everyday life.

Similarly, Bornowsky’s paint reaches across tiled surfaces, using ‘pattern matching’ to orient each unit within the context of its tessellation. These illustrative rules end up resembling iconographic arrows or fragments of typography—as in the quantum of happiness enjoyed by a country’s inhabitants and the means of its future improvement (2025)—bridging the abstractions of mathematics and semiotics. The character of his paint further strengthens these knotty overlaps. Egg tempera is an ancient picture-making technique, which the artist employs alongside equally ancient earth pigments, steering mathematic connotations away from abstract objectivity and toward something meditative or embodied. Each brushstroke accumulates without ever achieving full opacity, leaving behind traces of finite labour even as the image gestures toward boundless repetition. Other pigments are chosen for their elementary nature: cadmium, titanium, and zirconium are all periodic elements, molecules that cannot be broken down any further—and yet, there is no limit to what can be built from their permutations.

Instead of stretching paint across a primed surface, Stockholder applies colour directly upon manufactured plastic and metal artifacts, which selectively spills over onto the gallery wall. These works are decidedly unframed—except when they reflect the architectural environment in which they are contained. In Cargo (2025), even language is reduced to material, the syntactical line of a sentence disrupted and reconfigured to produce new meaning through paraleipsis. Whenever her material seems to resolve into a singular identity, the artist cuts it off, instead focusing on blurred overlaps rather than clean separations, just as Bornowsky’s patterns seem to revel in the absence of a standardized grid. As still over time (2025) reaches beyond the gallery walls, we glimpse that each artwork’s framework is contingent: a knot of supply-chain relations that, if unraveled, would implicate the entire world.

The artists’ overlapping tactics of ‘picture-making’ give both practices a metonymic quality. Whereas metaphor operates through resemblance—one thing standing in for another—metonymy depends on adjacency and material connection. Stockholder literally draws lines across what we call nature and society, each hooked terminus acting as an anchor that clasps nearby objects in a continuous chain. Bruised Elbow (2025) features elemental copper and an amputated tree limb aligned with a plastic food tray. What do they have in common but everything? The tree evokes nature, yet this tree was cultivated, replanted among others to replenish clearcut tracts, while plastic has become ubiquitous within so-called nature. Her practice insists that there is no raw material from which to construct—only matter already shaped by culture, industry, and environmental pressures. Bornowsky’s work asks similar questions, to different effect. How can we conceive of infinity from within our decidedly finite perspective and existence? The procedurally-coloured, aperiodic patterns that comprise his work are subject to multi-stability—which is the optical condition of having several likenesses at once. For Bornowsky, multi-stability is universality, the common denominator of dissimilar perspectives is their difference and their ongoing interpretability. In this way, both artists’ works entangle the viewer, drawing us into a chain of causality that unfolds in simultaneously material and symbolic dimensions.

The eponymous question of the exhibition, is a knot helpful, cannot be resolved, even as the knottiness of contiguity cannot be denied. If a knot is helpful, it is only to us as individuals of limited perspective as a way to trace the connections between microscopic elements and global supply chains, between the human hand and the arc of history. A knot ties the world together, however provisionally, reminding us that every loop of understanding contains its own tangle.

Jesse Birch is a curator, writer, educator, and artist who was born and raised on Snuneymuxw territory (Nanaimo, BC). Jesse has lived and worked in Vancouver, Seoul, Kyoto, and Amsterdam, and in 2014, he returned to Vancouver Island to reconnect with his home community as Curator of Nanaimo Art Gallery. Jesse holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree (Photography) from Emily Carr University, a Master of Arts degree in Art History (Critical and Curatorial Studies) from the University of British Columbia, and he is an alumnus of the Curatorial Program at De Appel Arts Centre in Amsterdam. He sees curating as both a profession and a collaborative practice that brings artists and artworks into relation with people, places, and histories.

Eli Bornowsky’s (b. 1980, Alberta; lives/works New York) paintings and works on paper make use of mathematics and computer programs to generate unique optical rhythms. His solo exhibitions include Kings Leap (New York, 2024, 2021); Canton-Sardine (Vancouver, 2020); Burnaby Art Gallery (2014), and Western Front (Vancouver, 2010); with group exhibitions at Catriona Jeffries (2024); Kayokoyuki (Tokyo, 2021); White Columns (New York, 2021); Vancouver Art Gallery (2016, 2009); Richmond Art Gallery (2015); Burnaby Art Gallery (2013); and Ottawa Art Gallery (2014).

Christopher Mole is Professor of Philosophy, and Chair of the Cognitive Systems Programme, at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. He is the author of Attention is Cognitive Unison (2010), and The Unexplained Intellect (2016), and is the co-author of Understanding Mental Disorders (2019). He is currently completing a book that is provisionally titled The Precarious Being of Thought.

For over thirty years, Jessica Stockholder (b. 1959, Seattle; lives/works Nanaimo, BC) has exhibited widely in museums and galleries internationally. Stockholder’s recent solo exhibitions include the Museum of Contemporary Art, Toronto (2025); Es Baluard Museu d’Art Modern, Palma (2025); Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh (2024); Frac Normandie, Sotteville-lès-Rouen (2023); Kavi Gupta Gallery, Chicago (2021); and 1301PE, Los Angeles (2020). Recent group exhibitions include Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, Vaduz (2025); Musée d’art modern et contemporain, Saint-Étienne (2022); SFMoMA, San Francisco (2022); Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Turin (2021); Centre Pompidou, Paris (2021); and Deichtorhallen Hamburg (2019).

Documentation by Rachel Topham Photography.