Brian Jungen, Janice Kerbel, Jeremy Borsos, Liz Magor, Steven Cottingham

Arrows

January 30–March 14, 2026

The arrow of time is a concept describing the entropic duration from a known past to an unknown future. In physics, this process is irreversible, leaving us to experience time either through memory (we remember the past but not the future) or volition (we feel we can influence the future but not the past). But beyond the realm of thermodynamics, the arrow of time charts a crooked course. Memory is malleable and history is unsettled, constantly being rewritten across ongoing conflicts of understanding.

Accordingly, Arrows features artists who are attuned to the looping paths of human time. Many of the works may have the appearance of historical documentation or factual recordings, but all are in fact staged constructions that question the linearity of time and the impulse to narrativize. Together, artists Brian Jungen, Janice Kerbel, Jeremy Borsos, Liz Magor, and Steven Cottingham portray the conditions and causalities that guide the arrows of time—contesting how descriptions of the past become volitions of the future.

For much of human history, the arrow has served as an extension of force—no longer limited by arm’s reach but instead projected as far as the eye can see. In The Way of the World (2024), Brian Jungen repeatedly pierces an 18th century French colonial table with arrows. All shafts run parallel to one another, as if rained straight down, forming a dense thicket of wooden vanes sprouting multicoloured feather fletchings, with carbon steel points buried within the tabletop like roots beneath the surface. In this way, these arrows may signify seeds planted long ago now coming into bloom, a figurative reversal of centuries of systemic violence inflicted upon Indigenous peoples, or an arrow of time launched forward only to arc back upon itself. Complicating this entanglement is the status of the arrows’ fletchings: plucked from exotic birds whose movement, both as living creatures and as cultural materials, are highly regulated by governments internationally. Such protections, while oriented toward conservation, also preclude Indigenous practices that rely on the cultural, spiritual, and legal significance of feathers. Jungen’s deployment of them here evokes the unequal application of conservation, underscoring what is preserved and what is buried.

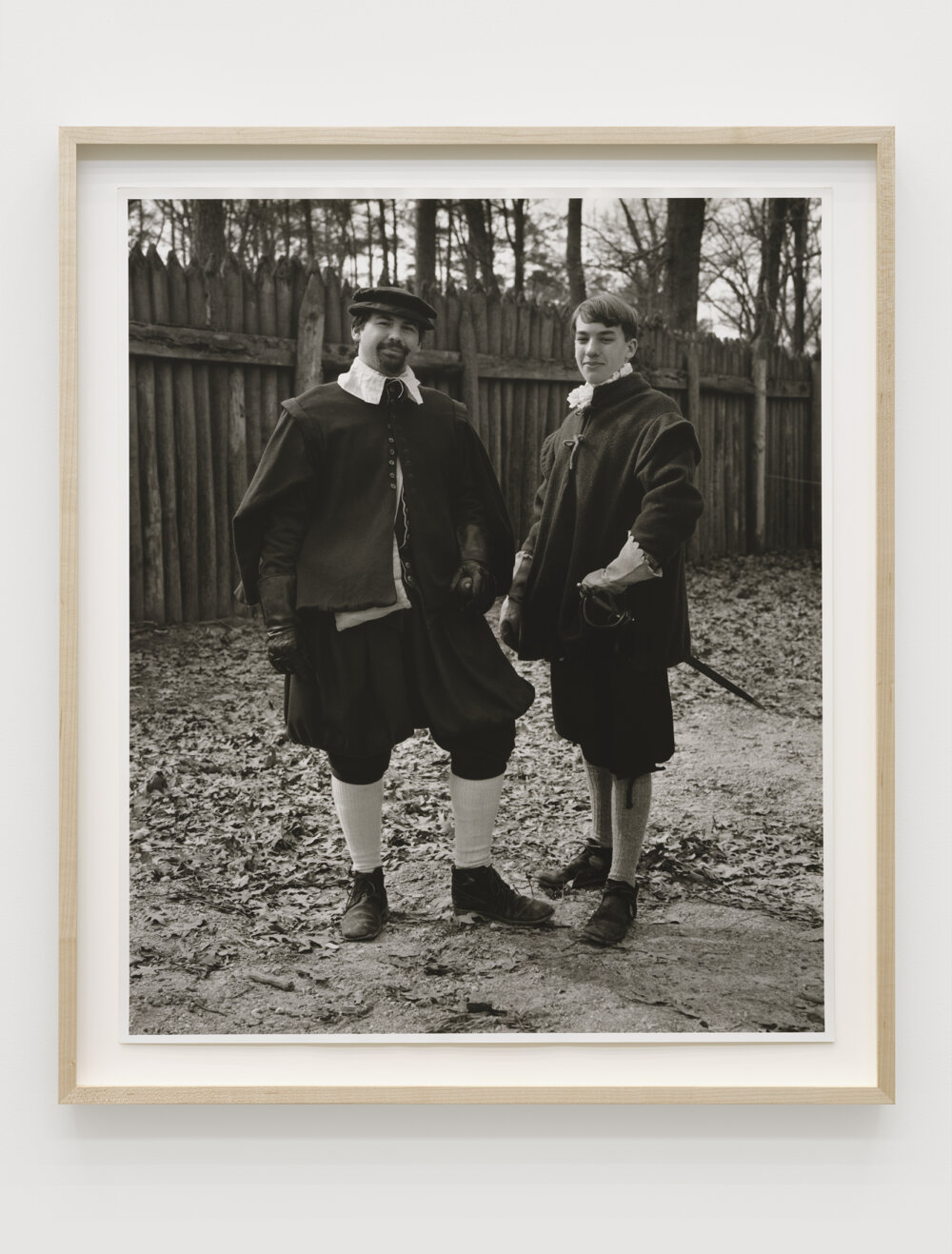

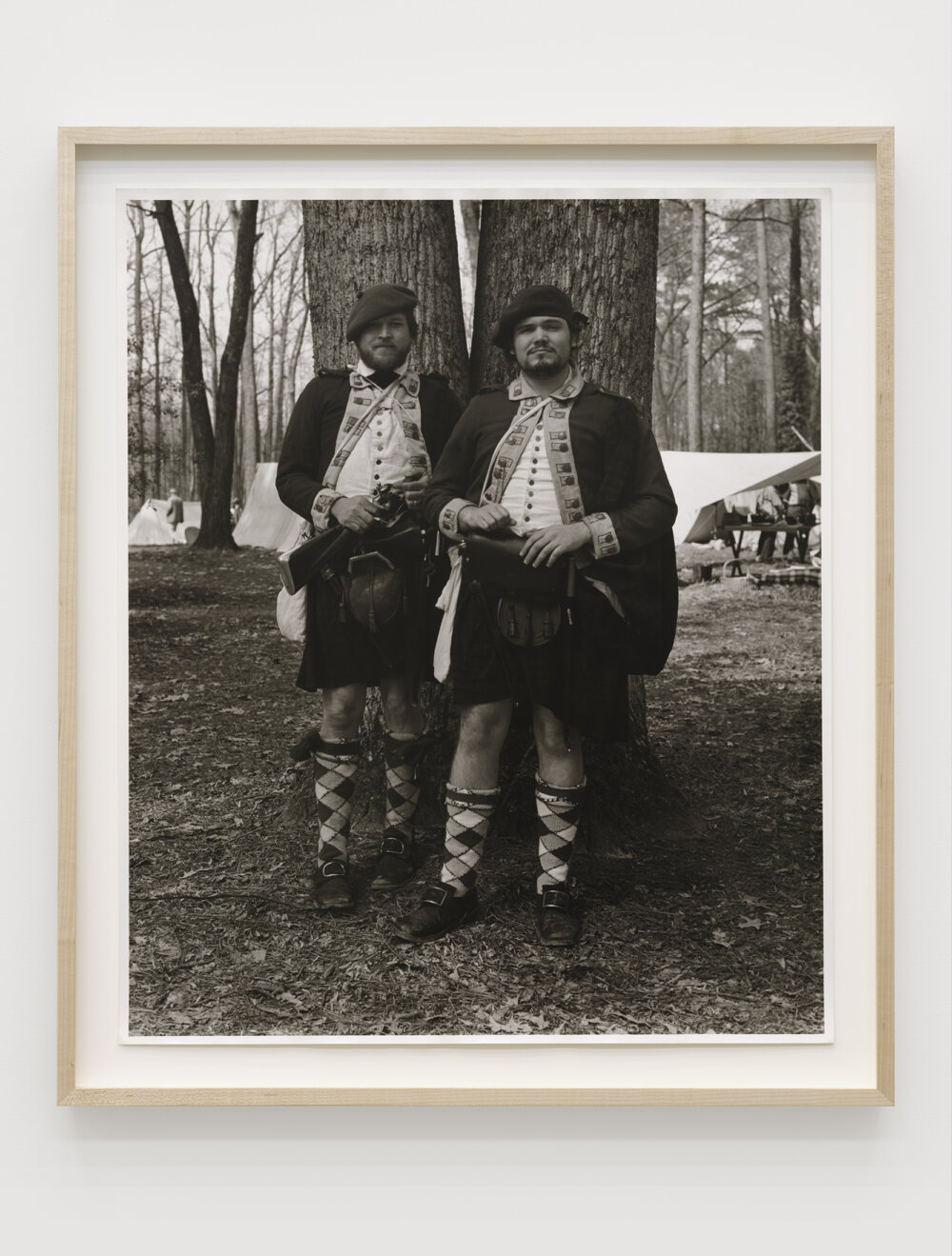

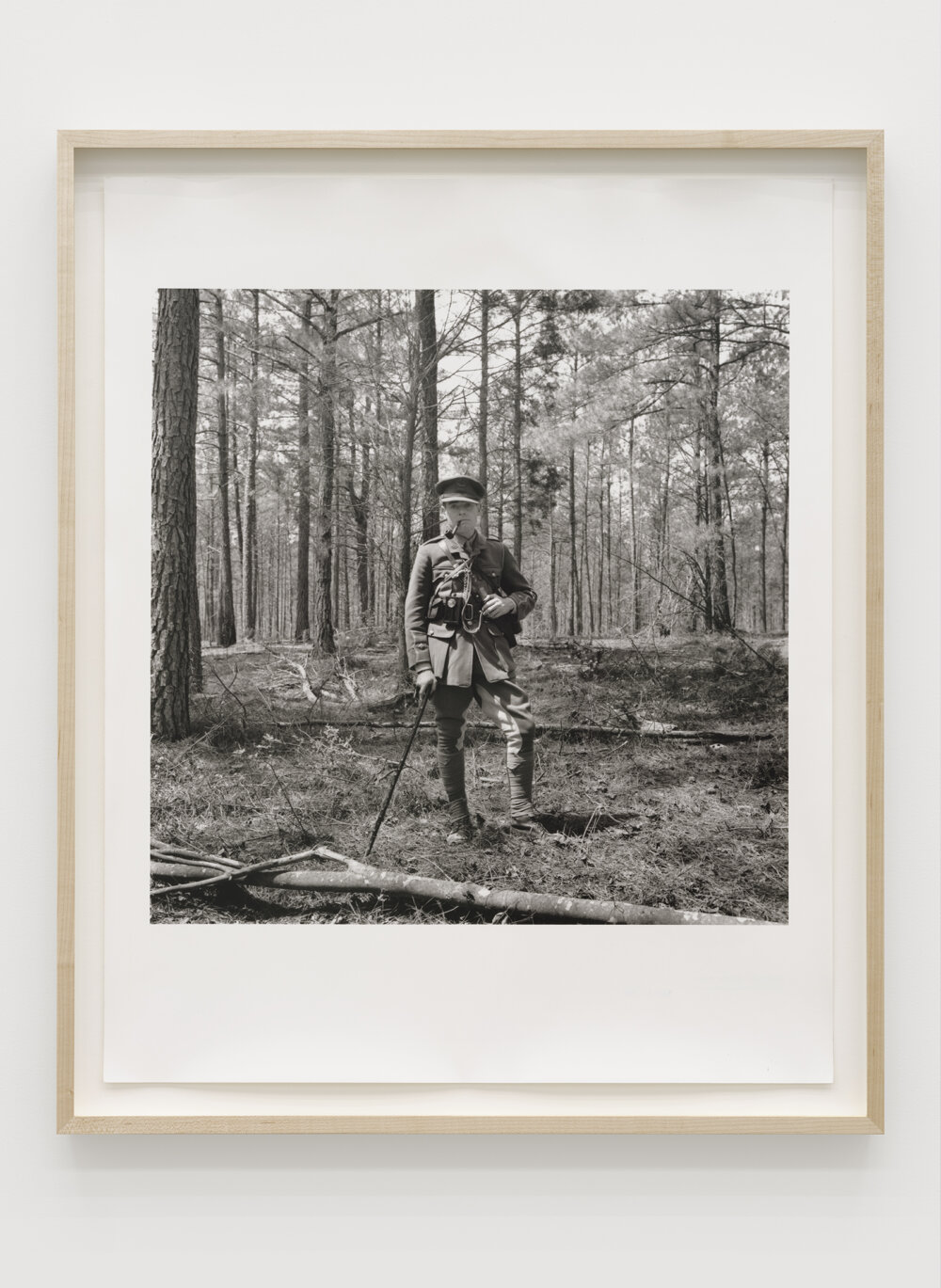

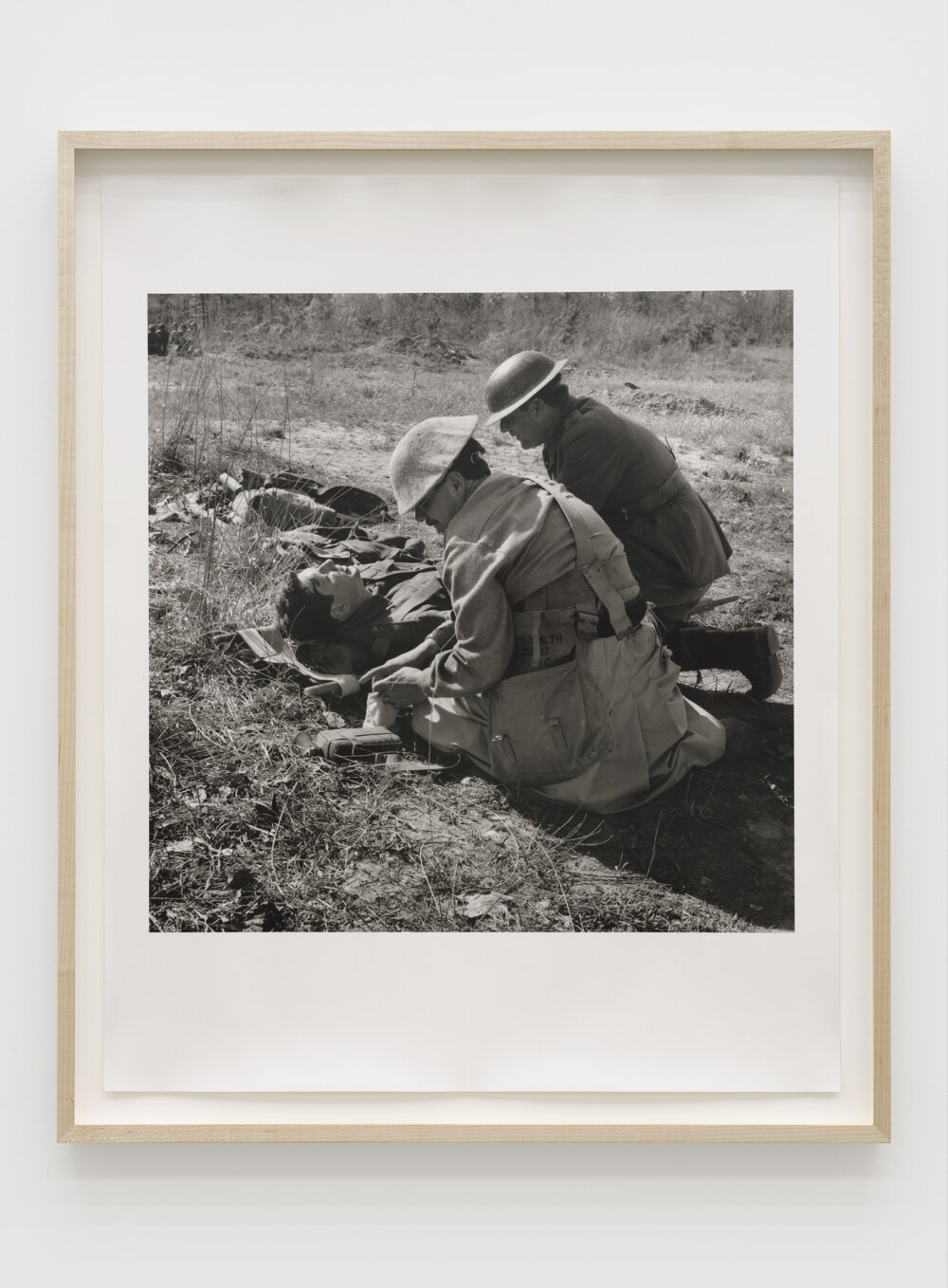

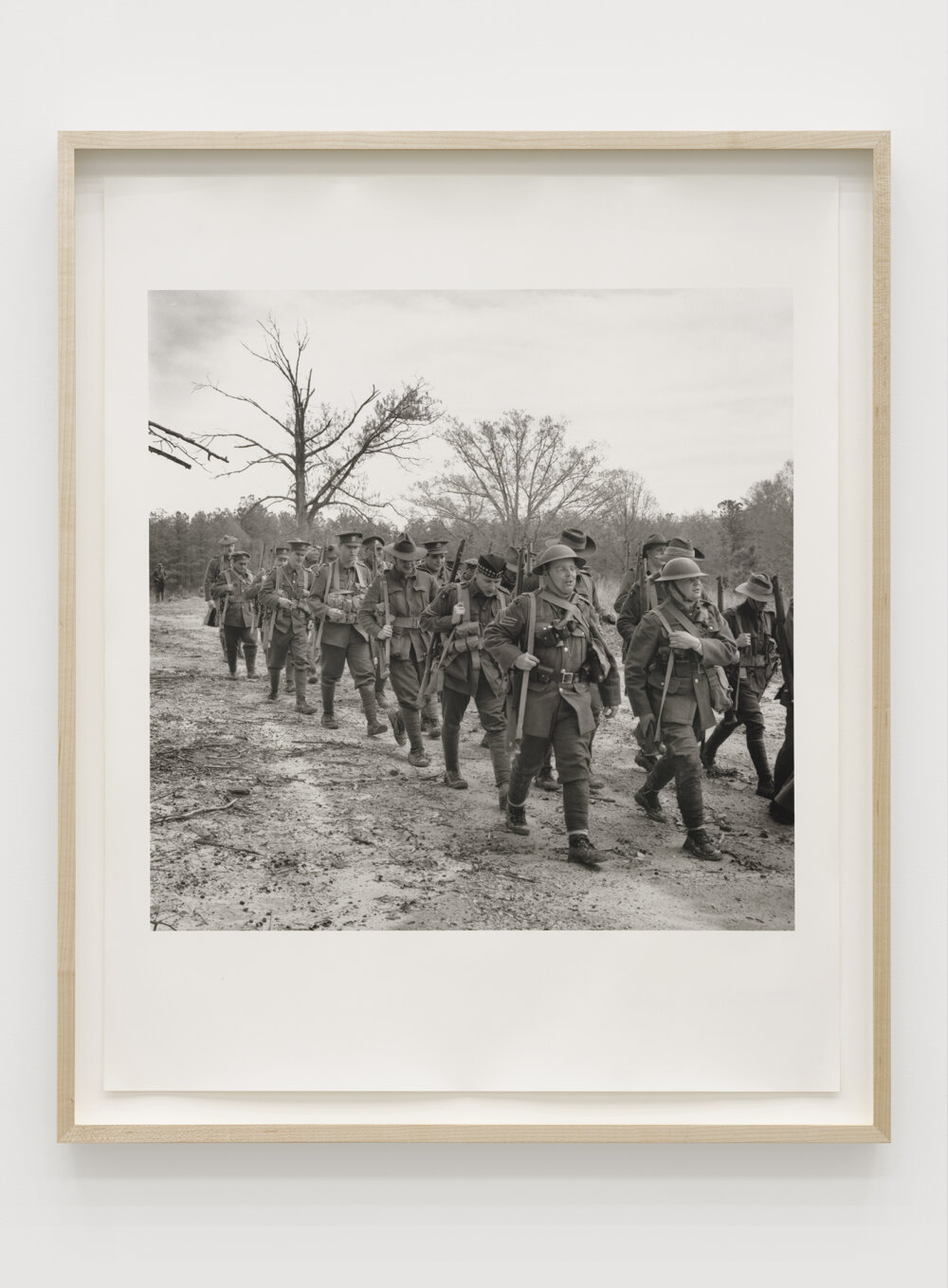

Similar frictions between historical events and modern-day retellings are central to the work of Liz Magor. In WW I Portfolio (1996), the artist documents historical reenactors who restage battles from the eponymous war. These performances are known for a level of accuracy that borders on fetishism, and it is difficult to surmise the eighty-year difference between the event and its photographic recreation by studying the actors’ fastidiously assembled costumes and weaponry. Rather, it is the image itself that gives away the illusion. Although black and white, the resolution seems too sharp, the frame too composed. Yet, it is precisely this illusory quality that reveals the truth of the image. History does not resemble the photograph, except in half-seen flashes; there is more verisimilitude in portraying the endurance of its myths than in pictorializing their subjects.

‘Lest we forget’ may be the adage of this conflict which has now passed from living memory, but how does the imperative to remember align with the impulse to rehearse and recreate? In Magor’s photographs—which also includes the series A Pair (1994), featuring coupled reenactors of various other wars—the arrows of time become homophonic eros of time. This can be understood as a libidinal attraction to live vicariously, especially in relationship to the wars that shape historical narratives. For Steven Cottingham, whose work draws on the recursive dynamics between military simulations and video games, the eros of time is present both in military training that relies upon consumer-grade software to rehearse conflict scenarios, as well as the hobbyist wargamers who seek exhilaration by imitating battlefield action. In Magic Circles Ringed in Barbed Wire (2024), Cottingham explores the back-and-forth crossovers of entertainment and defense industries—filmed within a manipulated video game where a virtual journalist reports on the wargame unfolding around her—while photomontages depict the virtual environments and hallucinatory practices found within a Canadian Armed Forces base. By emphasizing the role of simulation within contemporary military operations, these works ask whether a culture of pre-emption and preparedness does not end up painting the target around the arrow.

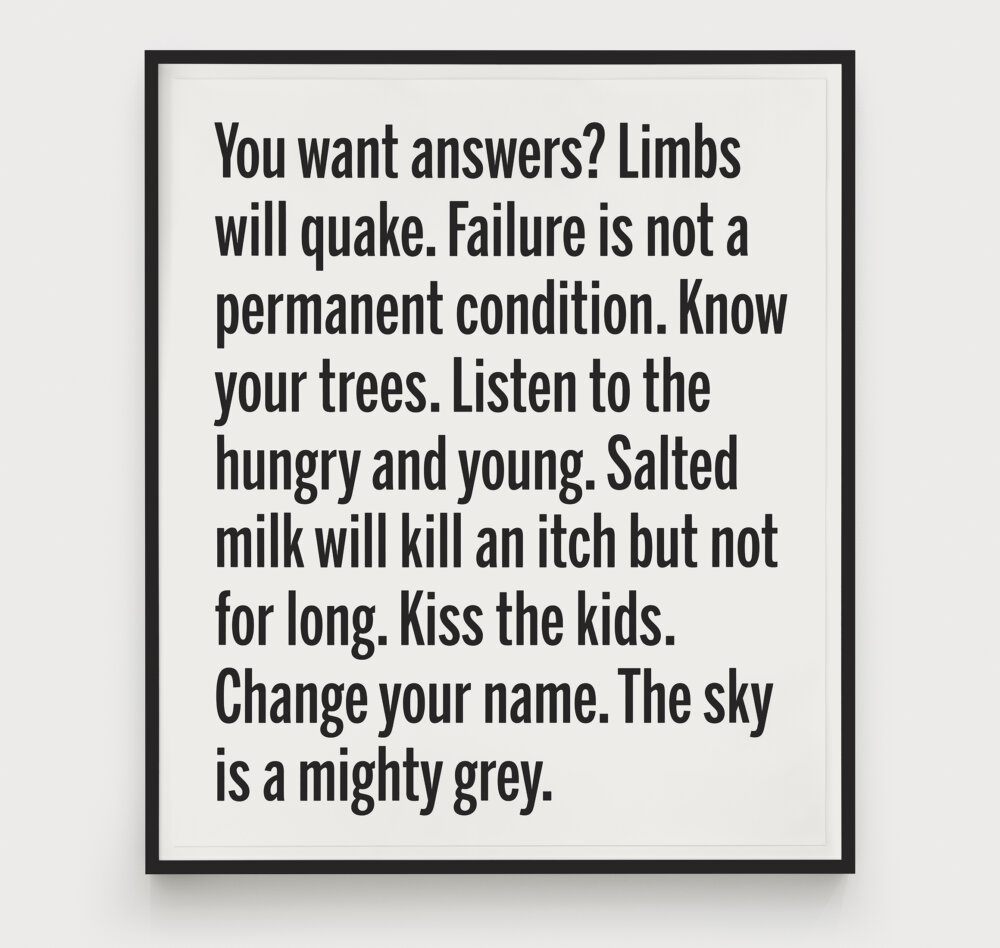

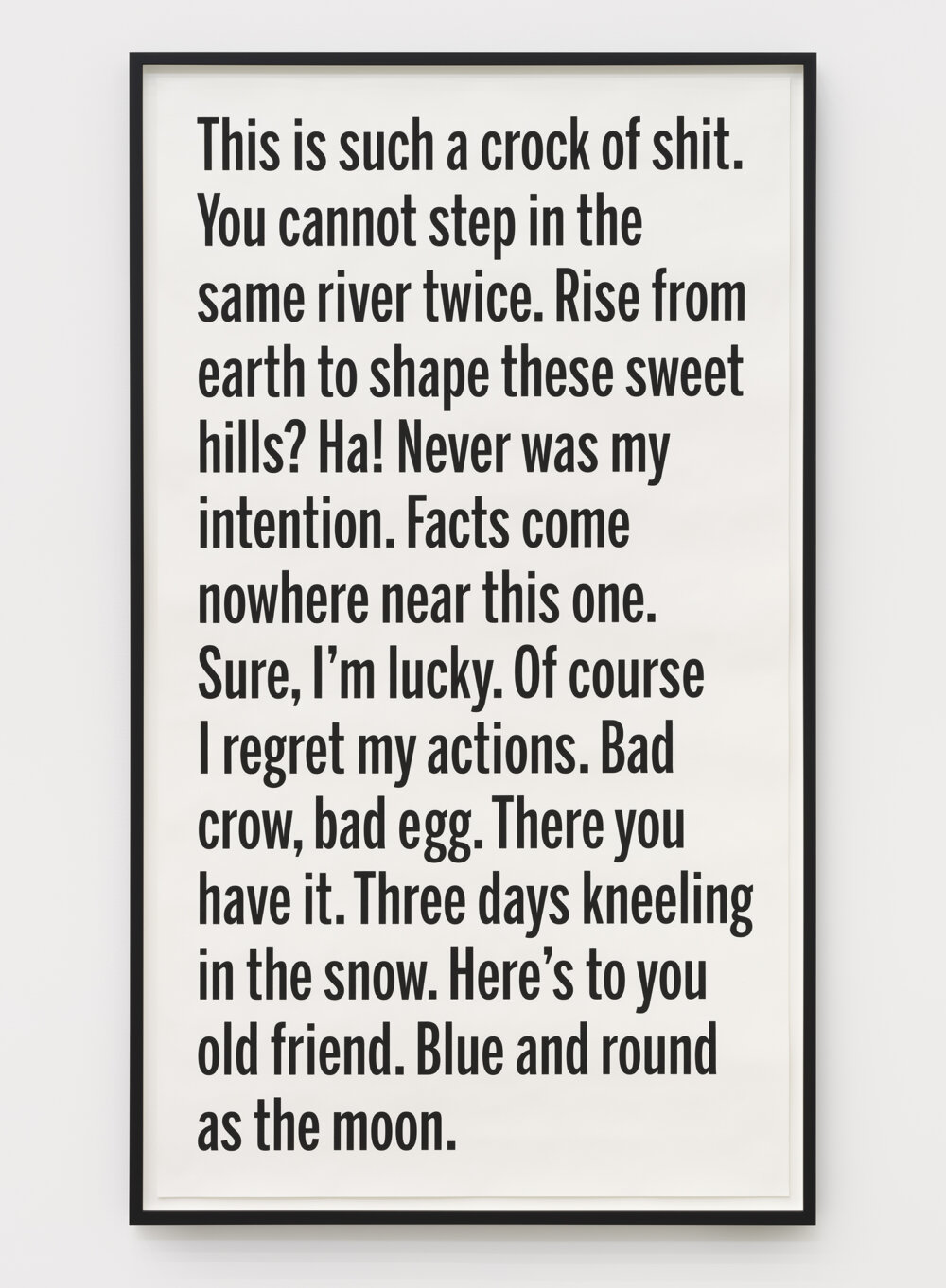

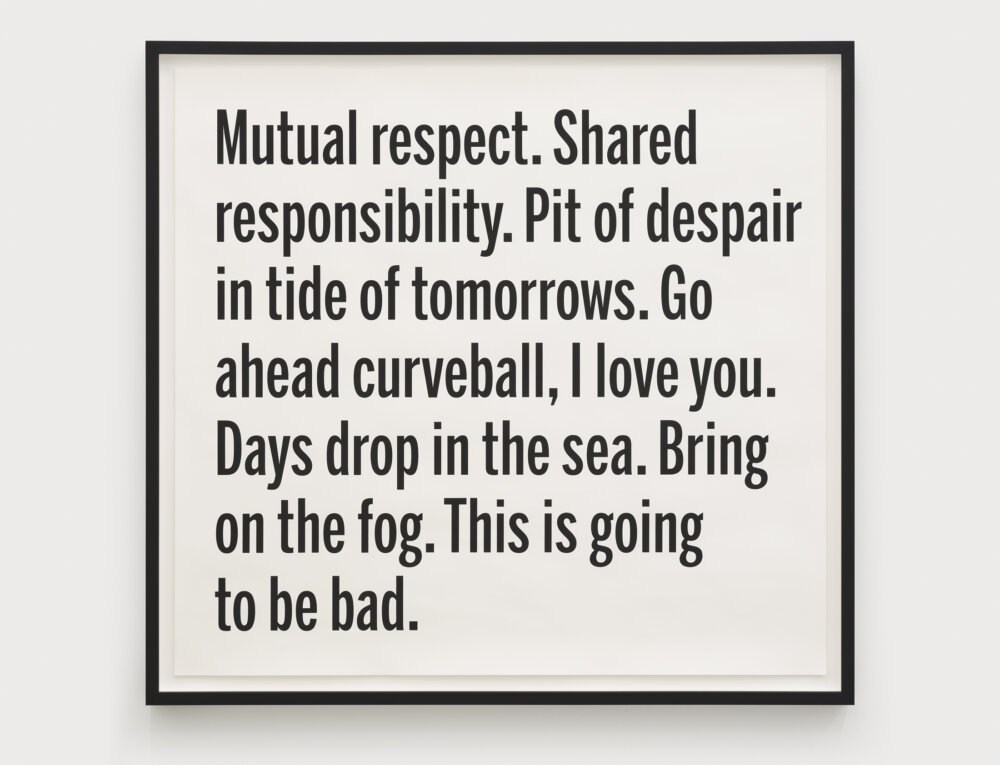

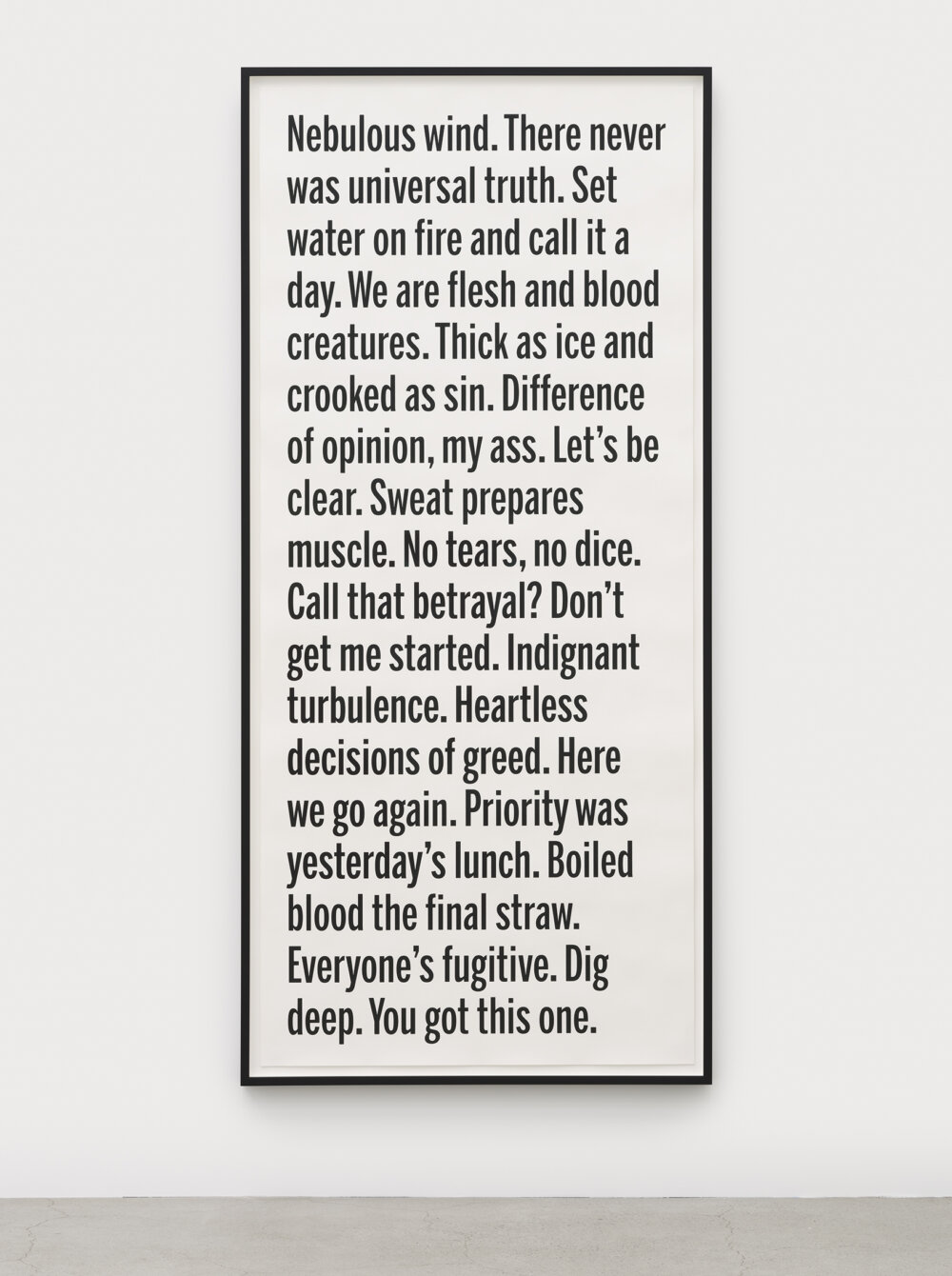

History may be written by the victors, but it is destined to be reinterpreted by its spectators. What remains are fragmented narratives—which circulate by way of school curricula, personal testimonies, and conspiratorial forums alike. Janice Kerbel’s Rants (2025) comprise numerous one-liners and non-sequiturs agglomerated into literal walls of text. The pronouncements use the language of authority, an aggressive tone that captures attention through performative soliloquies. Certain phrases flare up amid the attenuated idioms: ‘Time teaches nothing.’ ‘You cannot step in the same river twice.’ ‘There never was a universal truth.’ But the dense and ragged typeface reads less like what would be carved in stone or stamped in press, and more like what would be pasted upon a billboard. The result is a sense of time propelled not toward resolution but toward accumulation: a temporal arrow shaped by consumerist society and oriented toward absence, urgency, and desire.

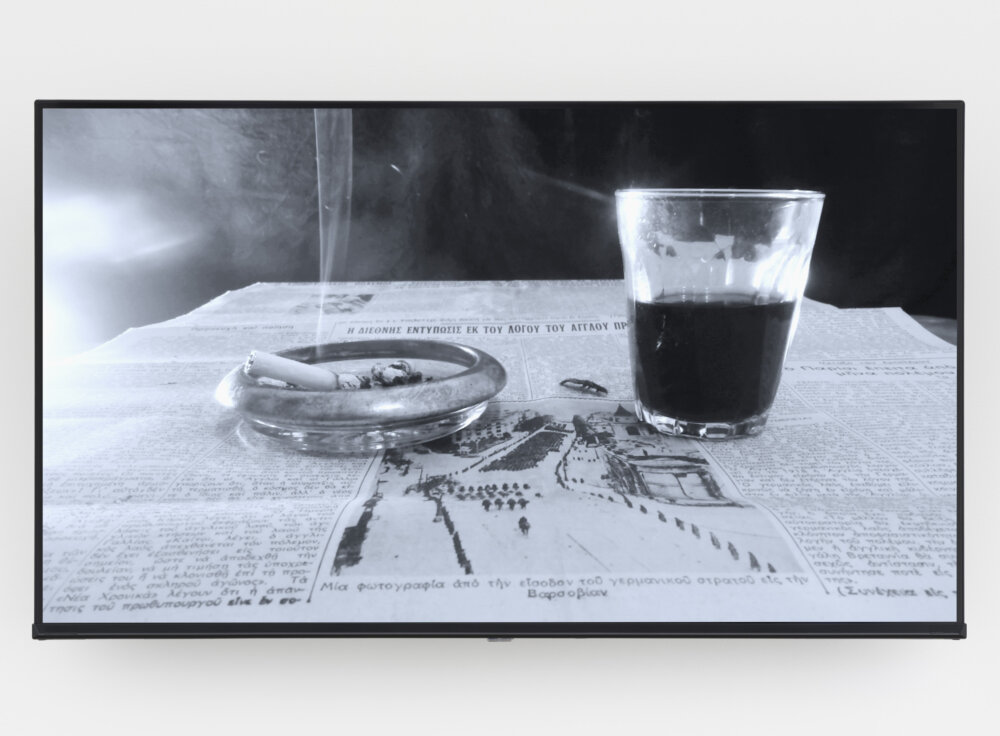

In contrast to the accelerated rhetorics of authority and rehearsal elsewhere in the exhibition, Jeremy Borsos’ work dwells in temporal slack—where history persists as atmosphere rather than narrative. 9/39 (2024) depicts an inky black beetle crawling atop a brittle newspaper, slowly circumambulating a glass of wine and still-lit cigarette. The titular report on Nazi Germany’s incursion into Poland is printed in Greek, forming an abstract and arid landscape for the wandering insect. A similar framing characterizes both The Bootblack (2025), where a mundane act of maintenance unfolds against a backdrop of political tensions, and Europe’s Unity Secures Your Freedom / Europa’s Einheit Sichert Dein Freiheit (2025), in which a penknife acts on a pencil until one begins to resemble the other. At the sharpened point of this utensil, time’s arrow appears to narrow toward order and volition, momentarily warding off the forces of entropy. Yet, as in Magor’s work, the image ultimately gives way to illusion, revealing the distance between historical events, their mediation, and the reconditioned forms through which they persist.

Across these works, history emerges not as a stable record but as an ongoing field of contested projections. While appeals to the past often seek a kind of moral clarity, the artists in Arrows explore how historical narratives are continually produced from the conditions of the present. By adopting tactics of documentation, reenactment, and indexicality, the works in this exhibition expose how such accounts are constructed, rehearsed, and weaponized in advance of their outcomes. The arrows of time are irreversible but not immutable: change begins in entropy.

Documentation by Rachel Topham Photography.