Eli Bornowsky – Walking, Square, Cylinder, Plane, NOVEMBER 26, 2010–JANUARY 22, 2011

Eli Bornowsky

Walking, Square, Cylinder, Plane

November 26, 2010–January 22, 2011

Western Front, Vancouver, Canada

Walking, Square, Cylinder, Plane features a new body of paintings that have come out of Eli Bornowsky’s dedicated studio practice in the past six months. Compared to his previous works, a turn can be seen in the artist’s output. Previously, Bornowsky’s canvases assumed a relatively polite size and played on the repetition of similar geometric motifs, with slight and energetic variations in size, texture and colouring. What connects his older and newer work is an obvious concern with the optical movement that each image is able to create in the eyes of its viewer.

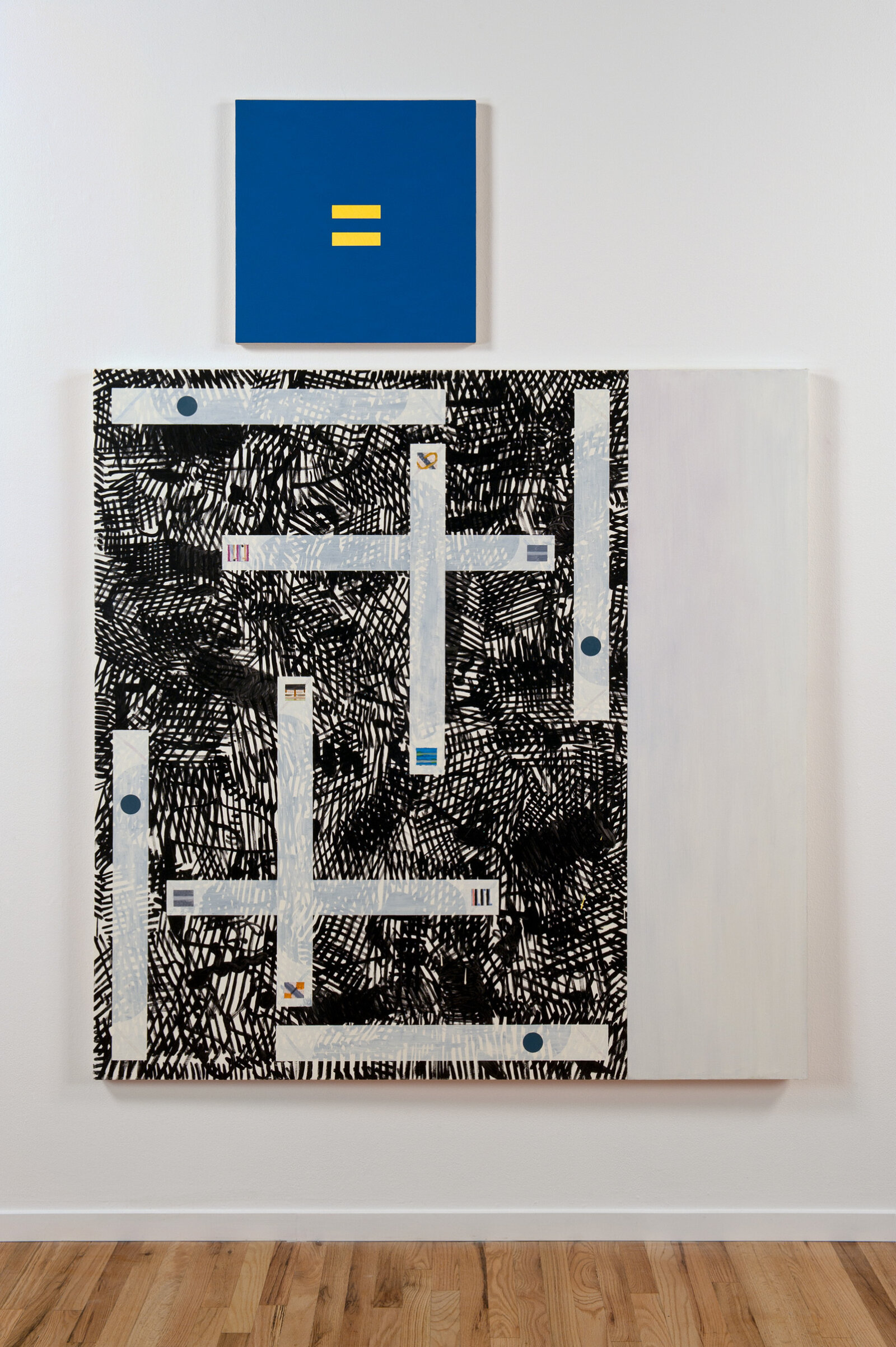

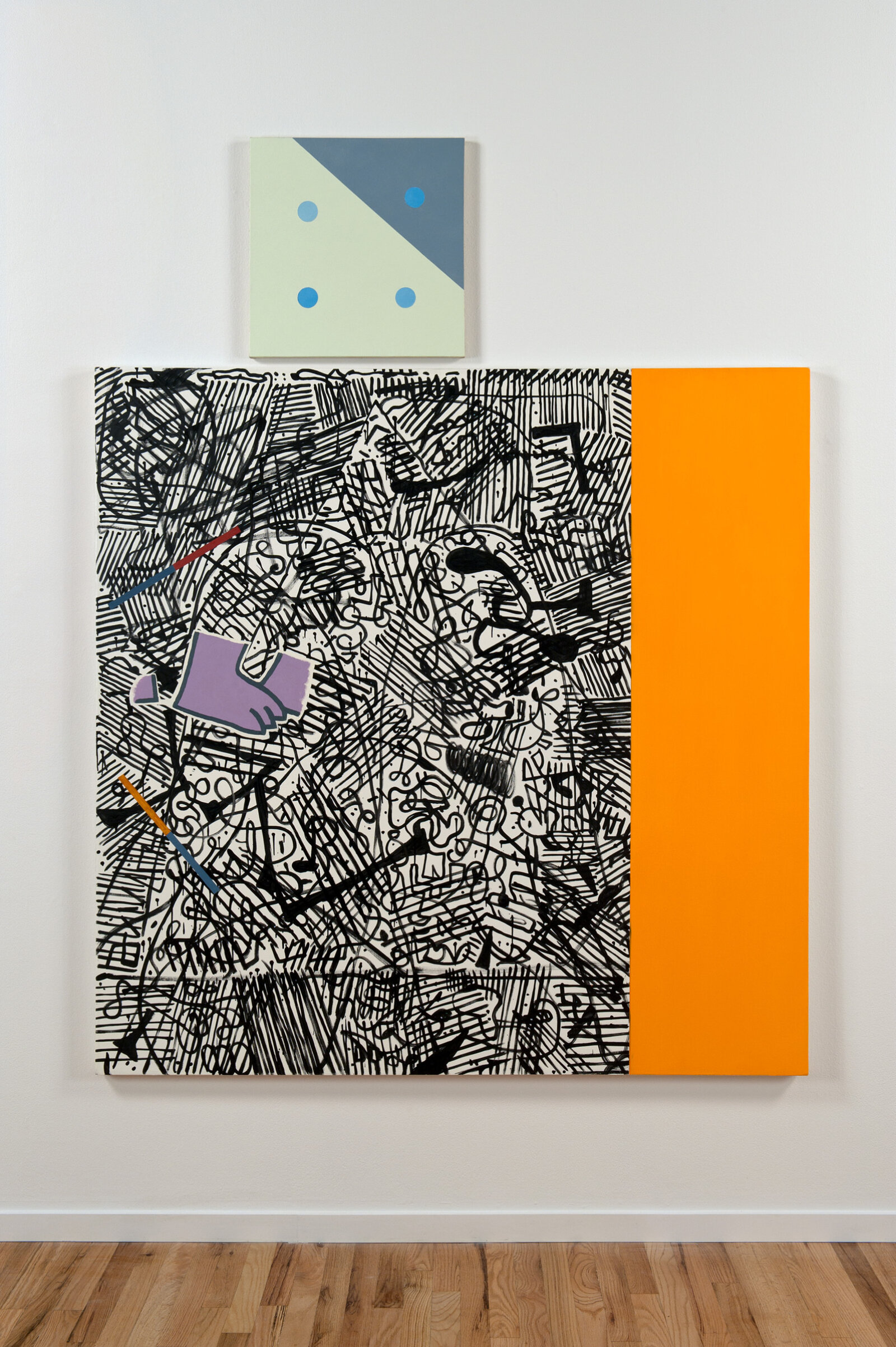

These paintings by Bornowsky have grown not only in noticeable size, but also in presence. The larger paintings demand attention, as a play between several visual vocabularies takes place. This body of work uses a foundational schema to map a similar set of fields and elements in the composition of each work. Drawing from his early education as an illustrator, a field of black and white scribbled abstraction is a constant visual ground in each canvas. Noticeably in each painting, a confidently coloured stripe vertically stretches across either the left or right hand side or horizontally along the bottom field. A third and more varied motif of a figure rests between or on top of these compositions. A cartoon like purple foot, an irregular and textured shape or a small box containing its own miniature landscape, are just some of the figures that seem to offer concrete positioning for the eye. Each large canvas is crowned with an accompanying smaller canvas, which is positioned in no repeatable method, except to say that they rest above. These smaller canvases recall Bornowsky’s older works, both in size and content, but they further obfuscate the visual exchange that happens throughout each painting. The companion canvases introduce a sensation of both belonging and foreignness. They are a curious and constant reminder for you to go back, look again and once more negotiate the multiple grounds and fields within each work.

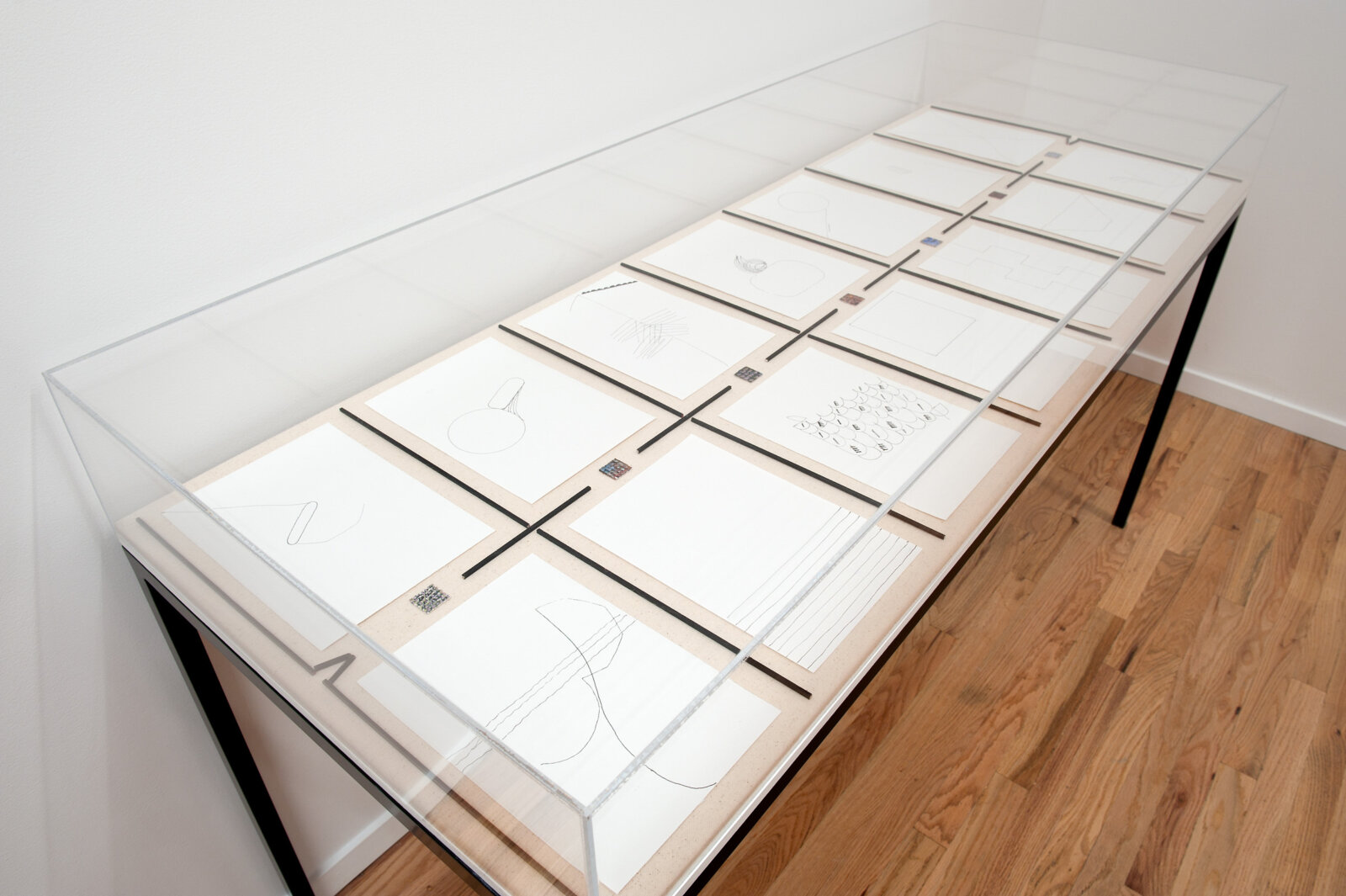

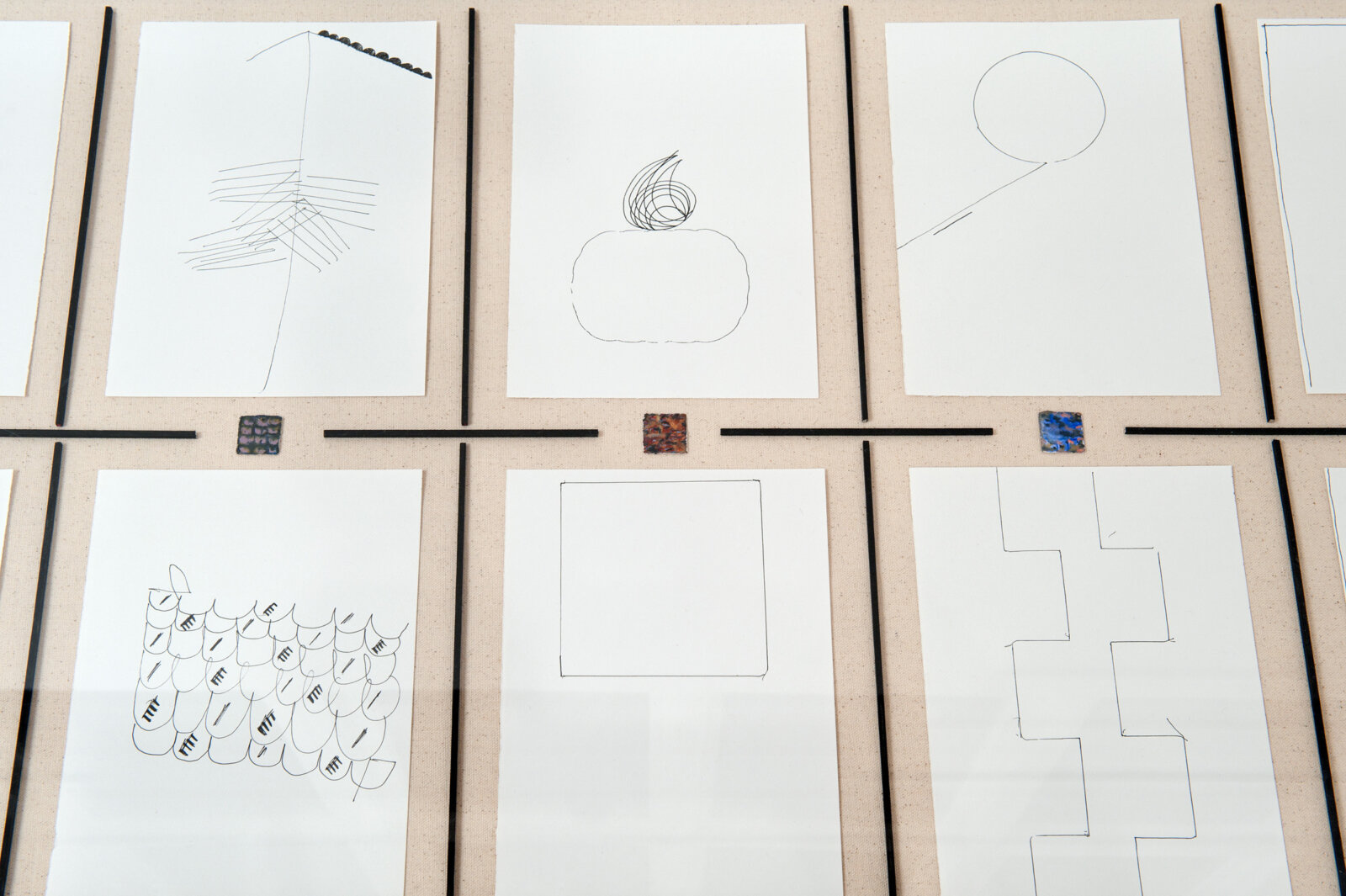

Also featured is Saturna Island (2010), the drawings in this work were made in an uninterrupted process while Bornowsky spent a holiday on the aforementioned Gulf Island. The immediacy of this line work is contained amongst a lattice of fine black borders made of balsa wood. While miniature abstracted watercolours have been cut out into squares and placed along the central axis of the configuration. More delicate in its approach than the canvases, what is revealed is the artist’s ongoing commitment to exploring abstraction amongst several mediums, forms and surfaces.

Saturna Island offers further access to Bornowsky’s intricate practice as an artist. Another part of his practice, though less well known, is his work with sound. These electronic compositions also concern themselves with repetition and variations in sequence, though in a more minimal manner. And, even more recently he has been producing a series of silent digital flicker films, which soak the viewer with rapid oscillations of crisp colours.

What Bornowsky has committed himself to across his various outputs is a continued study of abstraction and its necessity today. Of this need he has said concisely, “it continues to offer an alternative to the predominance of the cinematic in our visual culture.” This counterpoint to the cinematic refers to both representation in the image and also narrative formats. Instead, what Bornowsky highlights and seeks in his practice is the primacy of the experiential, and being aware and learning from a direct encounter with his work.

With his other forms of output in mind, trying to determine in which sequence to refer to Bornowsky’s practice—as an artist ahead of painter, or as a painter ahead of artist—is a delicate thought. One may ask the necessity of having to differentiate or define an artistic practice as such. When artists who paint do seem to achieve some acknowledgement, there is constant chatter of painting having to be popular, unpopular, heralded or reacted against. This often conflates and deters necessary and urgent conversations around a medium in which strong artists continue to work with and develop as part of contemporary practice. This talk around painting seems contradictory to common assumptions that artists are able to do anything they really want these days in their work. However, it is obvious that certain approaches to a contemporary practice still hold more water than others in public and academic spheres. In spite of this muffled medium hierarchy, which more than often seems to be discouraged from being addressed, attention should go to Bornowsky who paints in a studied, honest and truthful way. There is no suggestion of a conceptual approach, artistic conservatism or market driven influence when considering his choice of painting as his current ruling medium. Taking the opportunity to closely consider Bornowsky’s practice shows the value and necessity of the continued support of skilled artists who approach their practice with an artistic curiosity and sincerity.

During a visit to Bornowsky’s studio in the lead up to this exhibition, he had taped an image of Duccio’s Madonna and Child (c. 1300) next to his painting Vertical and Horizontal. As a source of inspiration or simply resonant in Duccio’s use of the horizontal ledge in the bottom field of the painting, this investigative thinking shows Bornowsky’s well calculated but also peculiar line of inquiry. This vastly disparate historical parring might not be so far apart on closer consideration. In the first chapter of Margot and Rudolf Wittkower’s 1963 book Born Under Saturn – The Character and Conduct of Artists, a western European historical narrative is drawn of how the painter rose from the class depths of tradesmen, guilds and craft to a distinguished position. They write that “The earliest painters’ guilds were founded in Italy [in the 14th century]... these guilds usually comprised related crafts such as glass makers, gilders, carvers, cabinet makers and even saddlers and paper makers.” Duccio surely had to contend with the conditions and environment that these guilds enforced. Some guilds “... assumed the right to destroy indecent pictures and punish their maker”, creating a situation in which it was “...not easy for an artist to assert his individuality or to be unruly.” This might be a situation with which Bornwosky could relate when measuring his practise amongst his peers, as he persistently pushes an approach to art making which might feel contemporarily déclassé. Regardless, his practice offers a visual language that appears remarkably urgent.

Equally, returning to this understanding of the craftsman, as Duccio was probably considered during his time, might be beneficial when considering Bornowsky’s practice as a whole. A better understanding might come from the observation of Bornowsky as a craftsman, working as an abstractionist.

Documentation by SITE Photography.