Christina Mackie – SEPTEMBER 21–NOVEMBER 2, 2019

Christina Mackie

September 21–November 2, 2019

Catriona Jeffries

Over the last 40 years, Christina Mackie has developed a complex, idiosyncratic language—concise and technical, yet intuitive and separated from narrative—through deep material engagement and experimentation in sculpture, watercolour, audio, ceramics, installation, oil painting, digital animation and video. In her work, Mackie combines and upends contemporary and historical materials and processes, leveraging our perception, natural phenomenon, and evolving technologies relative to our dominant structures of knowledge. Rejecting any romantic ideas of a return to material origins or historical processes, her first solo exhibition with the gallery comprises four bodies of work colliding and overlapping.

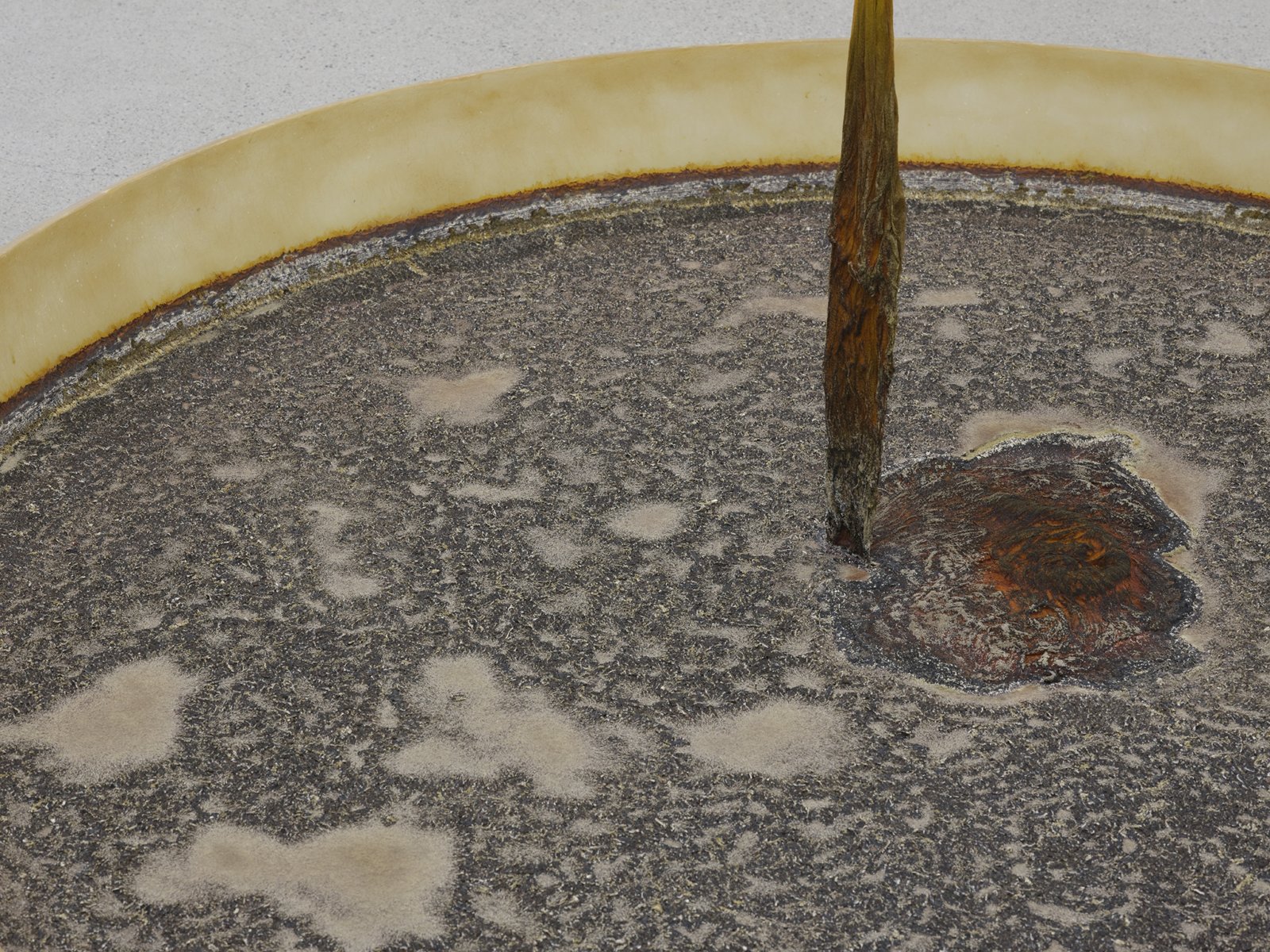

The central work in the exhibition space, Colour Drop, was commissioned and installed at The Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago in 2014. It began as a consideration of colour as subject, substance, and force, as well as the notion of ‘filtering light’, and attends to the ways in which colour is embodied in the behaviour or quality of objects in the material world. The conical nets in Colour Drop originate from a formative experience in Mackie’s childhood in the early 1960s when she encountered hanging plankton filters inside an ocean research laboratory, appropriately prescient for her own process in the studio and gallery. The form and scale, while rooted in experimental function, are here used for new investigations. Lowered from the ceiling by ropes, pulleys and weights, with their own carefully-considered material qualities, the hand-stitched silk cones are moved down from the ceiling to be dipped into shallow pools of coloured liquid dye, then hauled back into the air and suspended.

Weighing only a few ounces, the delicate net forms are stretched metres-tall, occupying significant visual and physical space, challenging the architecture that contains them. Translucent and reflecting particular frequencies of light via the dye-soaked silk, the nets capture and release our vision, controlling the viewer’s position, simultaneously asking to be looked down into and looked up through, as if the surface of the ocean was above us. The round trays of dye, their sedimentary liquids evaporating over the course of the exhibition, beginning to crystallize as they dry, becoming almost lichen-like in appearance. Placed around the trays are large polished shards of coloured glass, reflecting and consolidating the colours of the dyes: a new material reality for the reflected light.

Colour Drop, as much of Mackie’s other work, confronts our presumed mastery of knowledge, logic and information. If a net or filter is used as a metaphor—beyond that of the mental processes involved in perception of colour and light—the idea of capturing, catching, or gathering a particular property of a material expands to how we filter and mediate information every day, implicating contemporary data filtering systems and aggregation commodities such as social media and personal, mobile technologies.

“…the diamond net… the entire range of the universal determinations of thought… into which everything is brought and thereby first made intelligible.” (Hegel’s Philosophy of Nature, 1830.)

In the 19th century, Hegel proposed the diamond lattice of a net to describe a foundational principle of logic, introducing a key concept that the Western world has confidently operated with and within for centuries to explain how humans come to understand the empirical world and make it intelligible to ourselves. Here, Mackie asks us to question a fundamental cultural structure. Her work and their corresponding perceptual complexities allow multiple questions about the presumed solid foundation of this logic, and the relation of ourselves to the sea of information and data that we are enmeshed within.

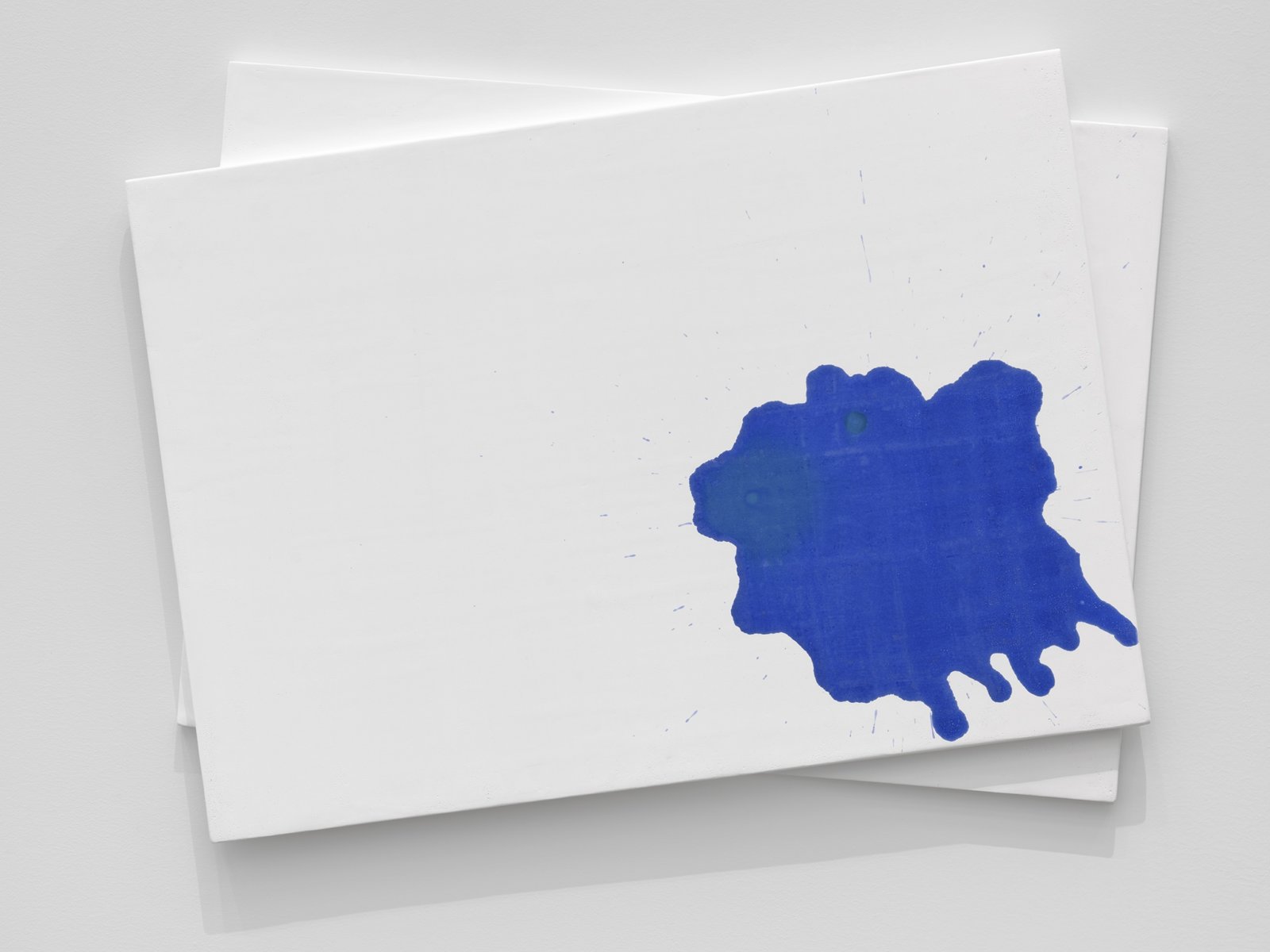

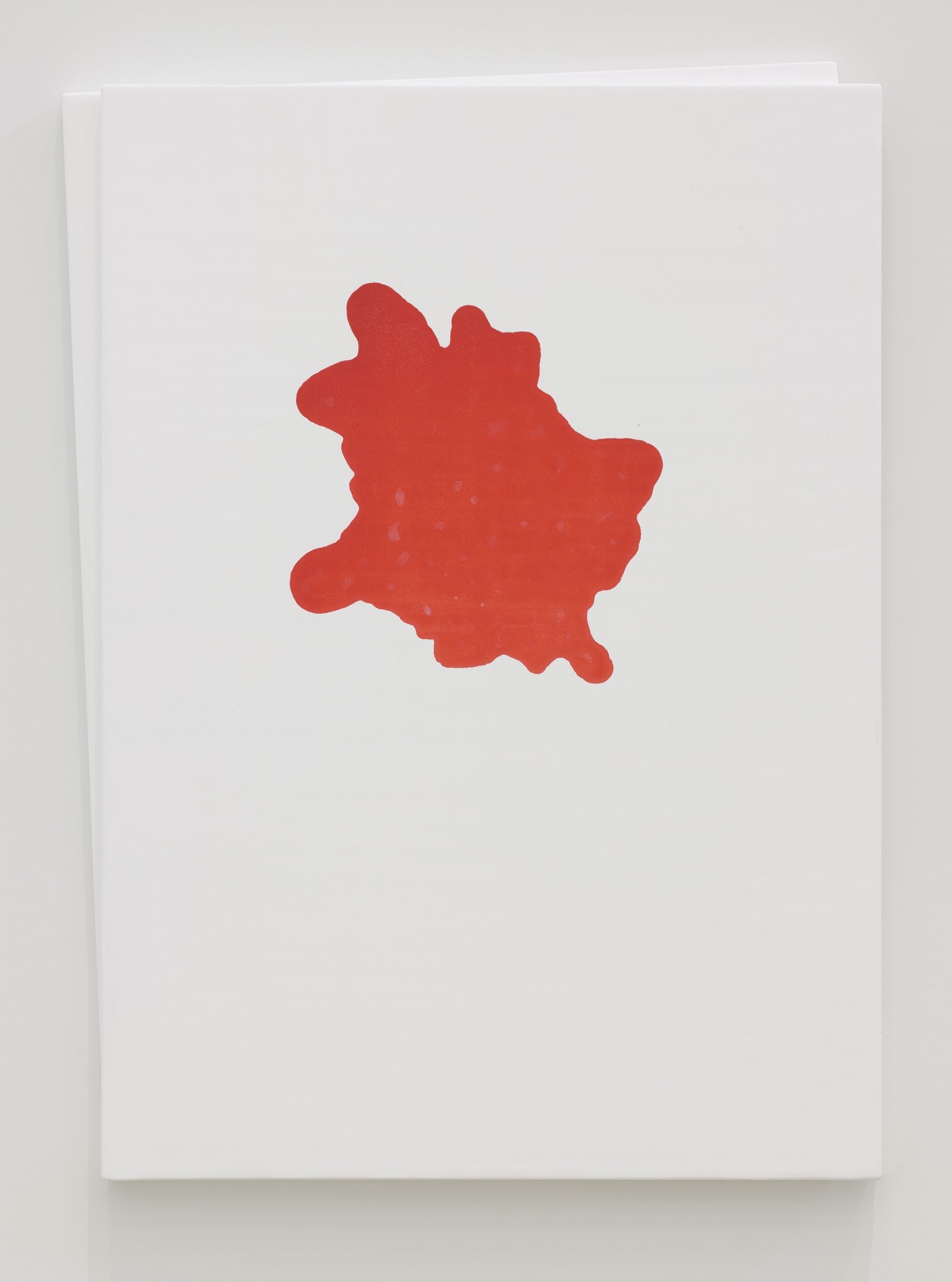

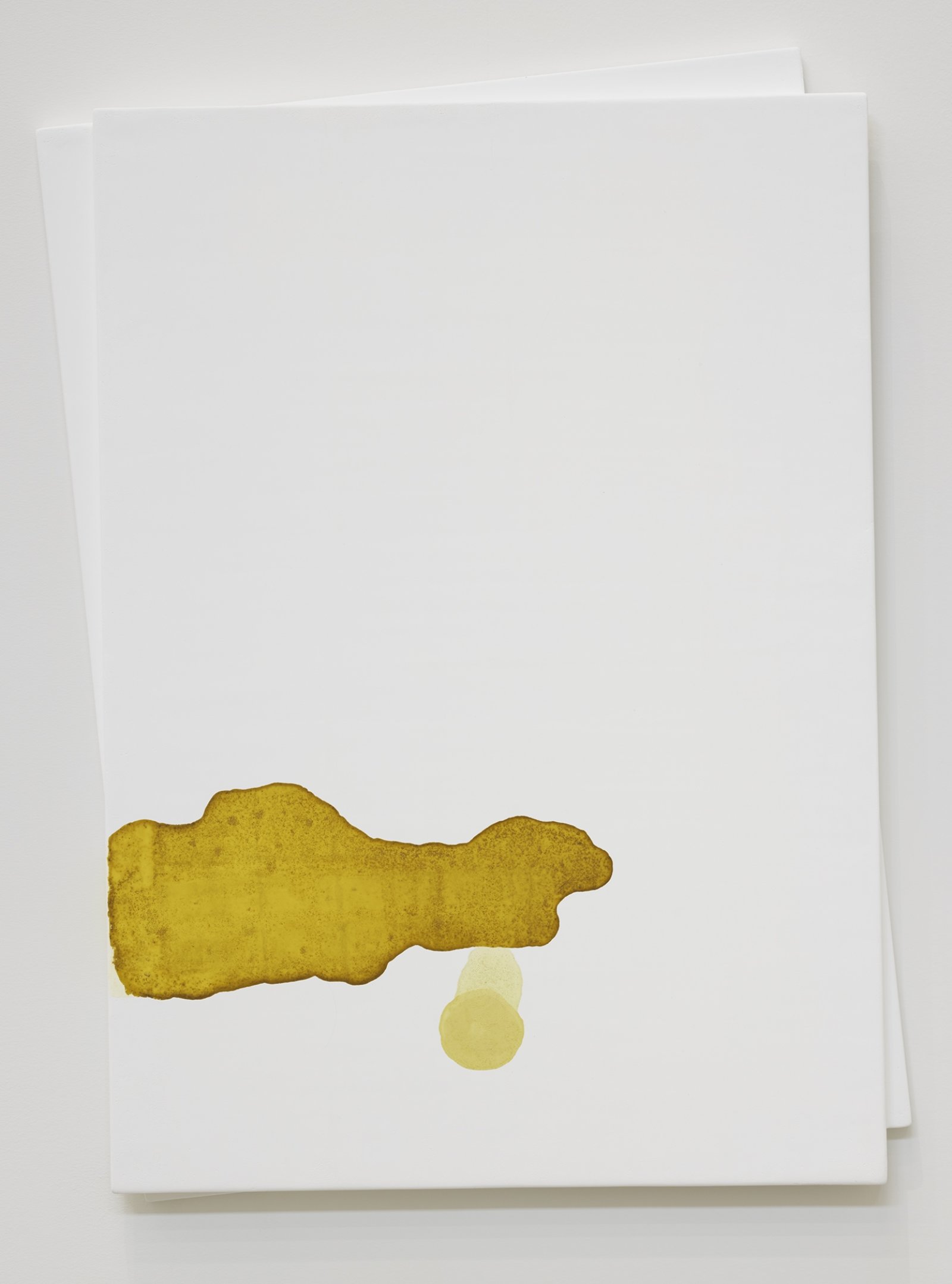

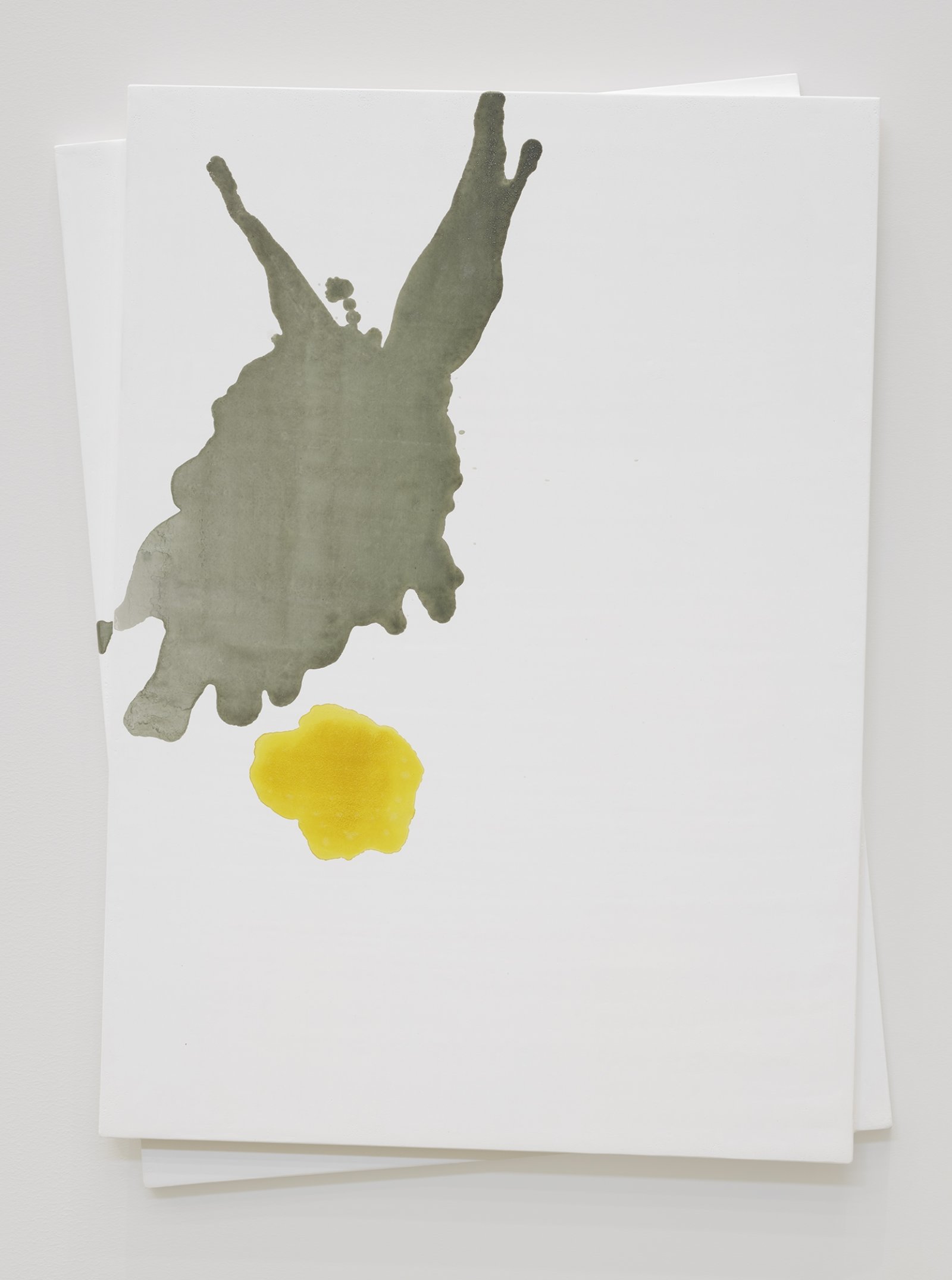

Five wall-mounted panels, each with two surfaces obliquely stacked and merged by twenty-five coatings of gesso mixed with chalk, are not paintings in the common sense of the term, but are sculptures that look like paintings, or sculptures in disguise. Their shapes become graphic, similar to those computer software icons of piled paper that indicate multiple and distinct files; the digital mimicking the physical, here reversed. Working within a specific material reality, the cross-hatched brushstrokes of the chalk-infused gesso become more apparent against the pools of watercolour highlighting the material particulars of the picture plane, the liquidity of their own origin transferred, flowing here and there over the edge of the panels.

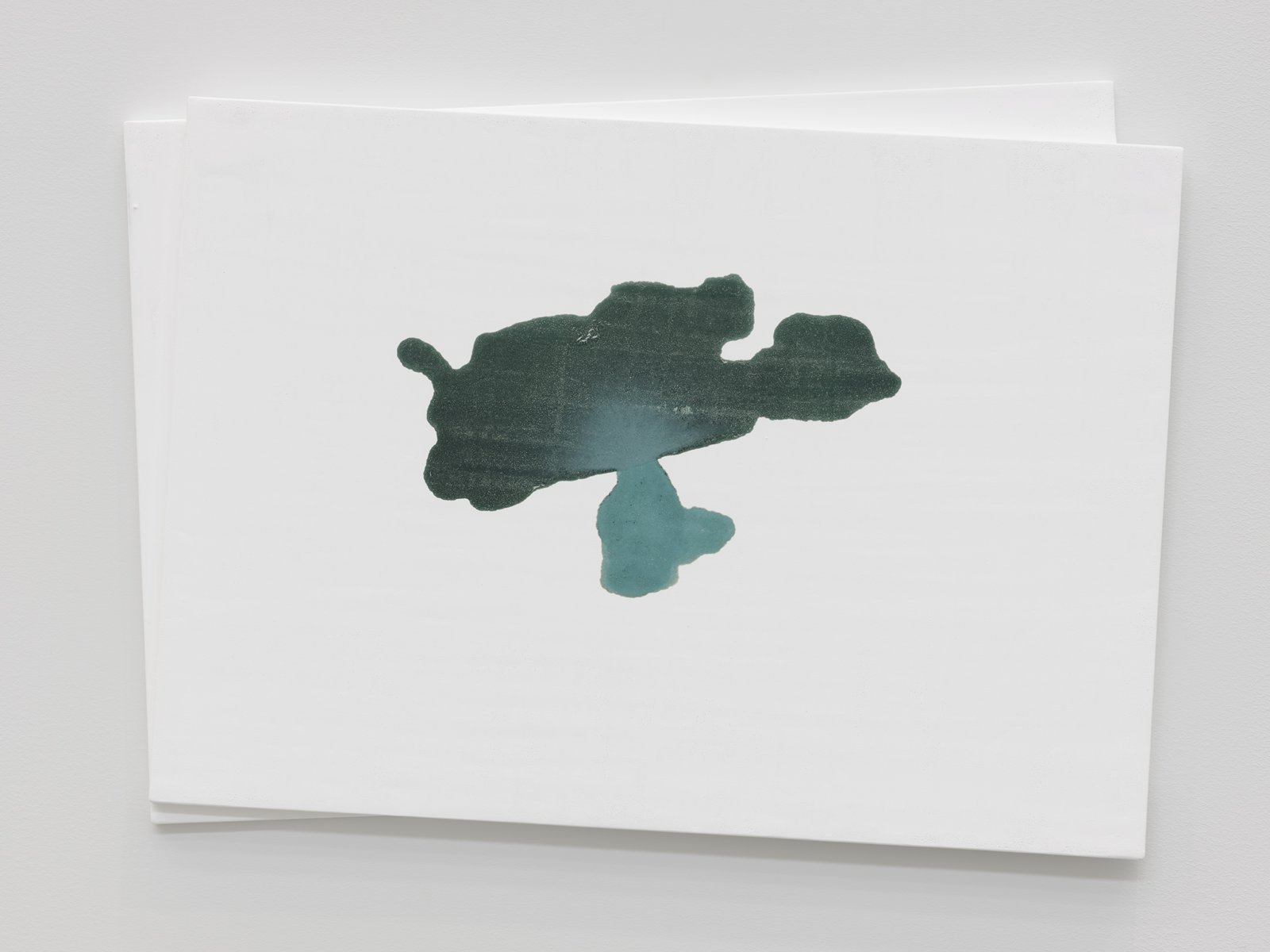

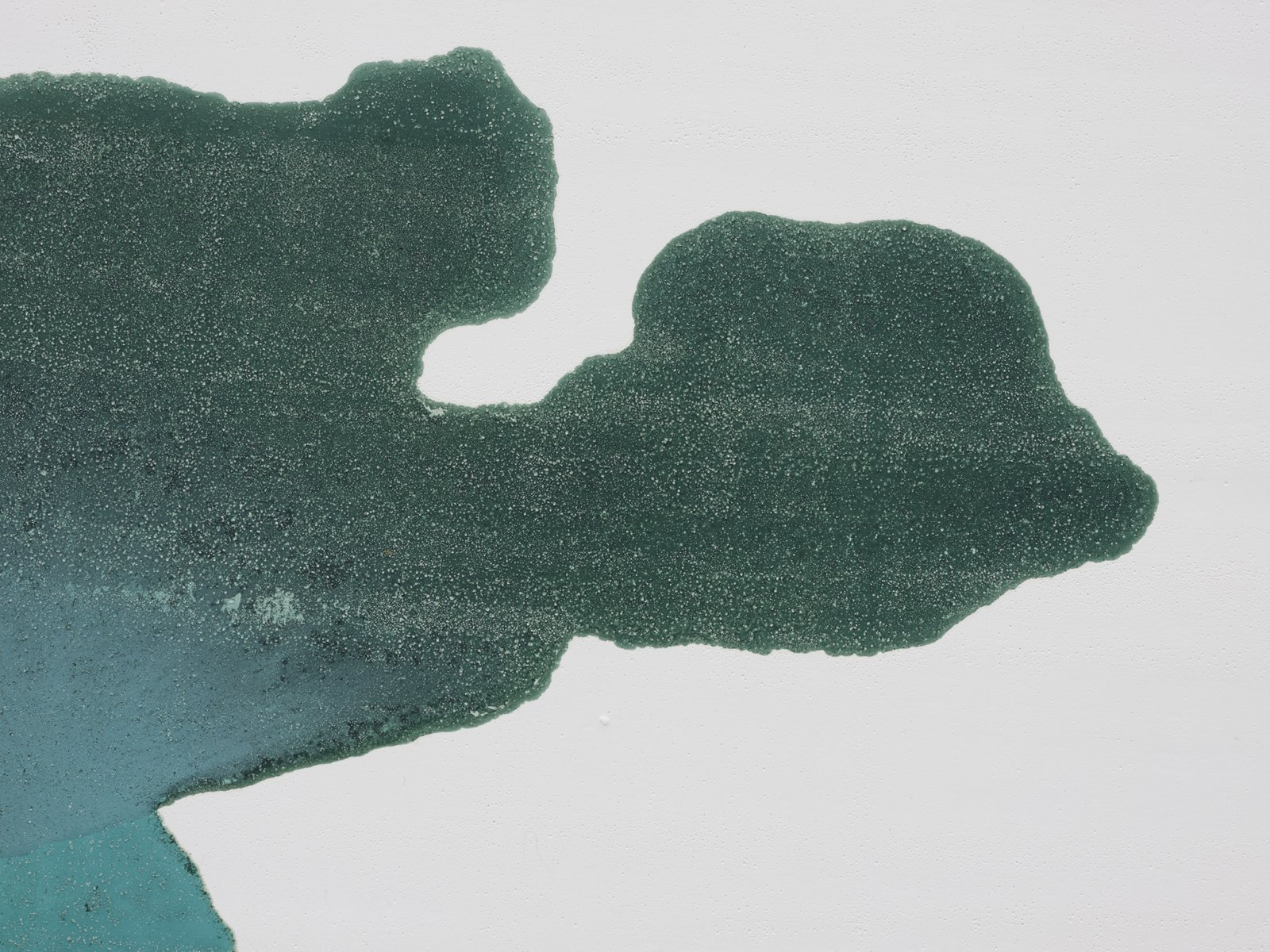

A set of interconnected ceramic works speaks to ‘clay management’, the technical aspects of their own thingness articulated in distinct shapes, seemingly rudimentary forms, almost examples illustrating the various material aspects or qualities of the clay itself, stuck together, fused with glaze to become one thing in fire. As the liquid pools of dye in Colour Drop evaporate to form crystals, glazes too become crystallized in their firing and cooling, forming a strength more than the clay itself, paradoxically considered the support structure for glaze as decorative ‘paint’. Contrasting the fixed nature of fired ceramics, the twisted and knotted textiles used as mounting structures are methods that deal with the reality of gravity, of the shape of the clay, and the objects relation to the wall. As with her other works, the often-invisible function or structure of object display is subverted and made prominent, suddenly in contrast and of as much import as the traditional locus of our attention.

Lastly, a new audio work is the first in a series of artists’ interventions in the gallery’s exterior courtyard exhibition space. For this, Mackie recorded the sound of the nearby train crossing bells (a regular auditory experience for visitors to the gallery), and edited and recomposed this recording in the studio. Broadcasting this new audio via speakers outside the gallery, it is altered yet familiar information cast back out into the space from where it came.

Here, now, let us consider the stingray and the StingRay. The former, a cartilaginous fish in existence since the early Cretaceous period, known for its flat diamond shape, hypnotic undulating locomotion and long venomous tail; the latter, a controversial cellular surveillance device used by law enforcement agencies across Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom. Similar to dragnet fishing in its disregard for what it catches, this technology, mimicking a cell phone tower, indiscriminately trawls and captures any and all audio, data and metadata from every cellular device within its net/range by design and force. The information captured from this mass ocean of data is filtered and organized, made meaning of and made use of.

Christina Mackie (b. 1956 Oxford, UK) lives and works in London, UK. Recent solo shows include People Powder, Spazio Culturale Antonio Ratti, Como, Italy (2018); The Judges II, National Trust Godolphin, Godolphin Cross, UK (2018); Christina Mackie: the filters, Tate Britain, London, UK (2015); Drop/And Bird/Frog And, PRAXES, Berlin, Germany (2014); Colour Drop, The Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, Chicago, IL (2014); Christina Mackie: The Judges III, Nottingham Castle, Nottingham, UK (2013); Bigger than a book, wilder than a tree: Christina Mackie and Jerry Pethick, Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver (2012); Painting the Weights, Chisenhale Gallery, London, UK, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, Denmark (2012); The large huts, Sculpture Court, Tate Britain, London, UK (2007); and show 50, City Racing, London, UK (1998). Her work has been included in numerous group shows, including Nature, Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver, (2018); Neither., Mendes Wood DM, Brussels, Belgium (2017); Constellations, Tate Liverpool, Liverpool, UK (2015); Molecular Etwas, Kunstwerke, Berlin, Germany (2010); Sillabario, Nomas Foundation, Rome, Italy (2010); Flutter, The Approach, London, UK (2006); 5five, VM Gallery, Karachi, Pakistan (2006); and Real World, Modern Art Oxford, Oxford, UK (2004).

Documentation by Rachel Topham Photography.