Abbas Akhavan, Geoffrey Farmer, Rochelle Goldberg, Kapwani Kiwanga, Duane Linklater

Unseeable

Sept 18–Oct 23, 2021

The unseeable – that which cannot be seen visually – is a boundary familiar to those in the physical and life sciences whose business is articulating a reality beyond human vision. Our shared condition in a global pandemic, altered by an invisible virus, has made the determinal yet widely ignored structures of our world articulated now more than ever. Our shared social, political, financial and historical realities are made glaringly present – their edges, fault lines and fissures highlighted, refusing to be ignored. What we once glossed over, took for granted in our numerous privileges, that which was unconsciously and consciously unobserved has been overwhelmingly made present. It is hard to imagine that which has been made visible can be unseen.

The recent works of Abbas Akhavan, Geoffrey Farmer, Rochelle Goldberg, Kapwani Kiwanga and Duane Linklater negotiate the limits of visible knowledge, not through the absence of the visual, but in their articulation of that which is not. The majority of the works were completed in recent months amidst shifting life situations and focused studio time facilitated by our new logistical restrictions and are the impetus for the exhibition.

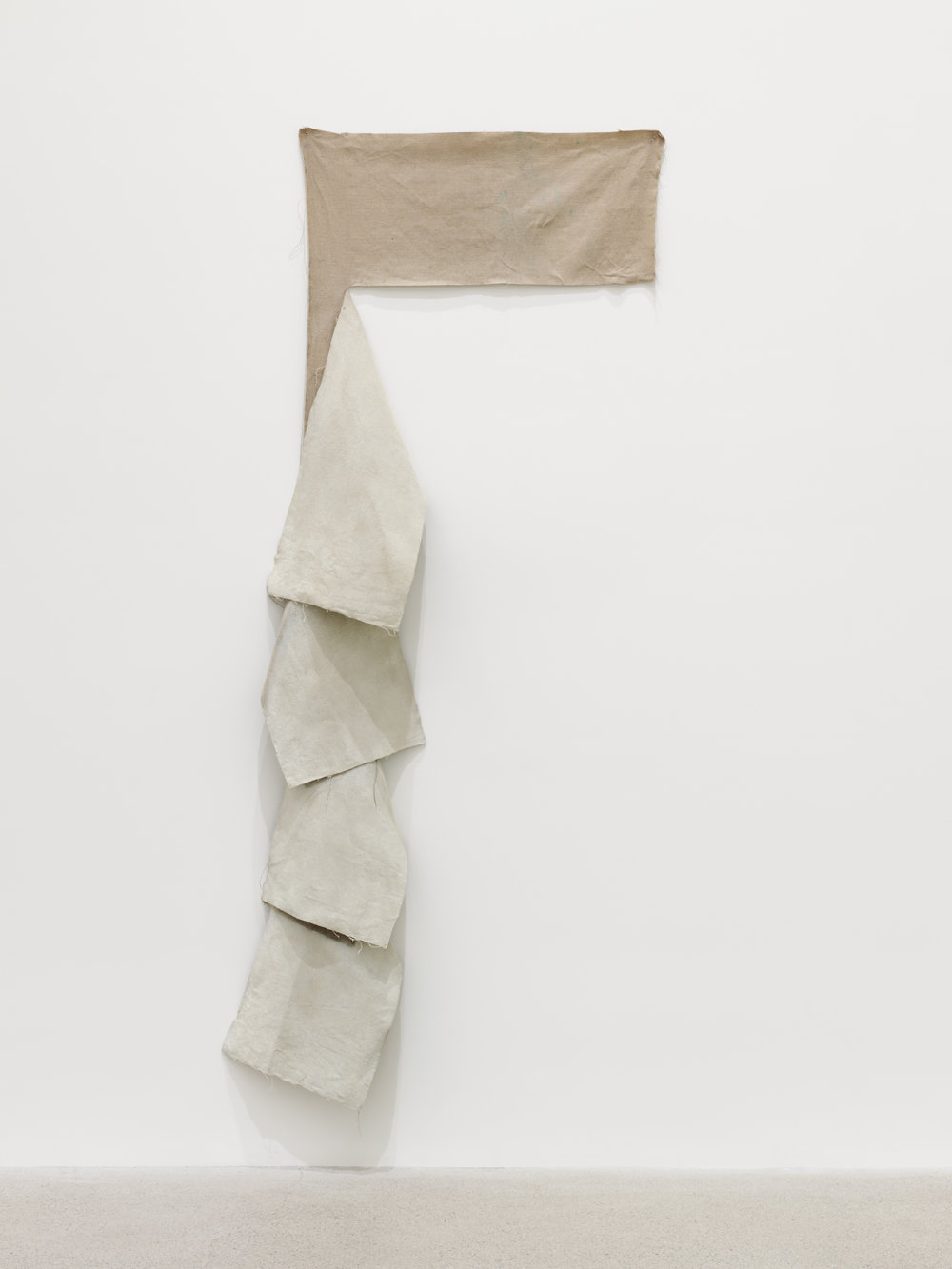

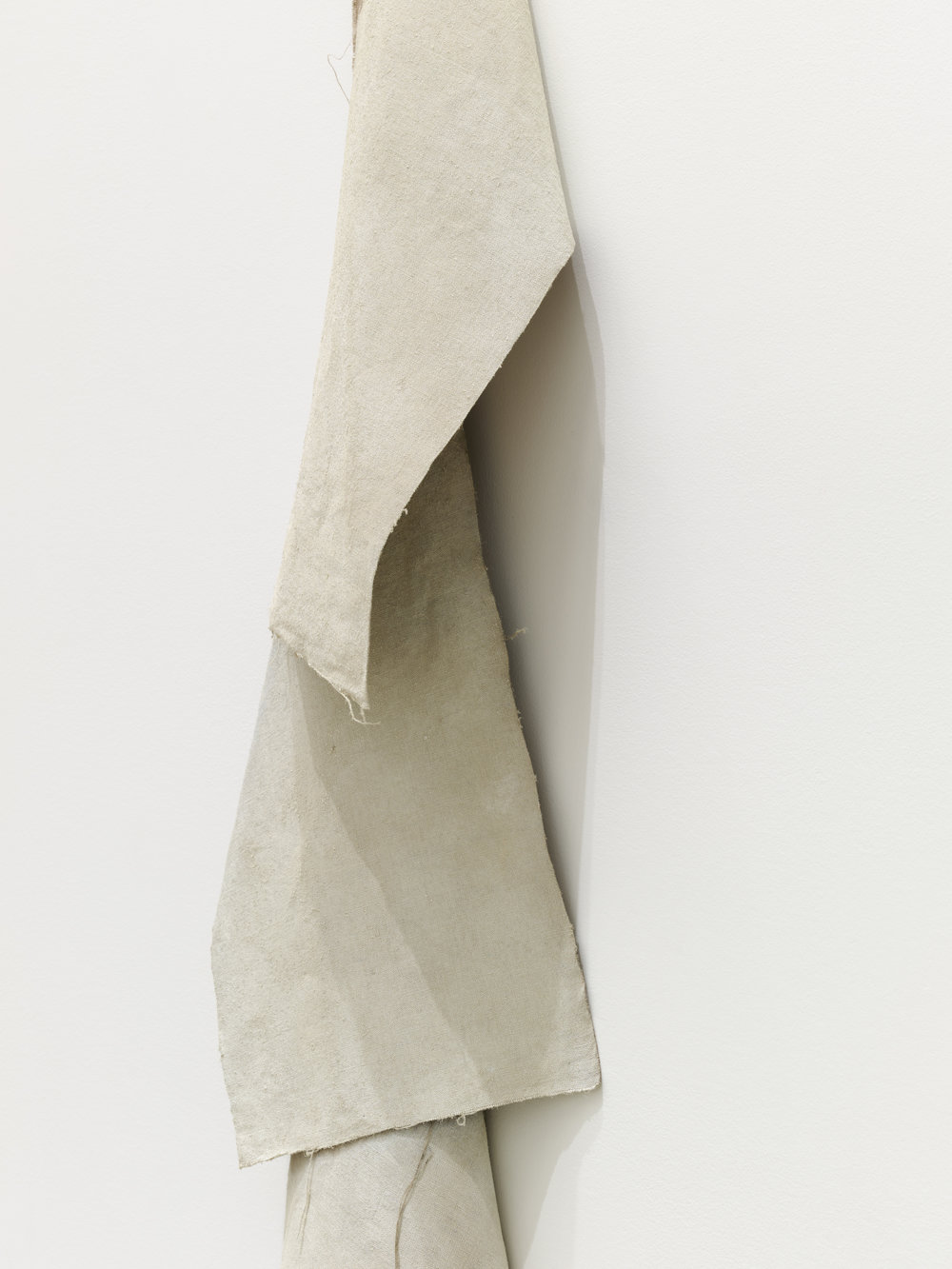

Abbas Akhavan’s most current series of subtle, poetic studio experiments utilize pigments and linen, exploiting their unique material particularities. For curtain, 2021, the artist references a Viennese theatre curtain, its undulating folds rendered flat in bold waves of pigment delicately applied to linen and hung directly on the gallery wall. While the familiar red curtain is designed to conceal what occurs behind it, then reveal activity in its absence, Akhavan focuses on that which is meant to remain "invisible", the curtain itself. Its suggestive mimesis leaves nothing but the gallery wall behind. In eighth square, 2021, a grid sequence is cut into pigmented linen but hung vertically from a single point, breaking down the modernist grid suggestion. The work invokes a chess strategy where a pawn reaches the "eighth rank" of the chess board to selectively become a queen, a queer reference for the artist.

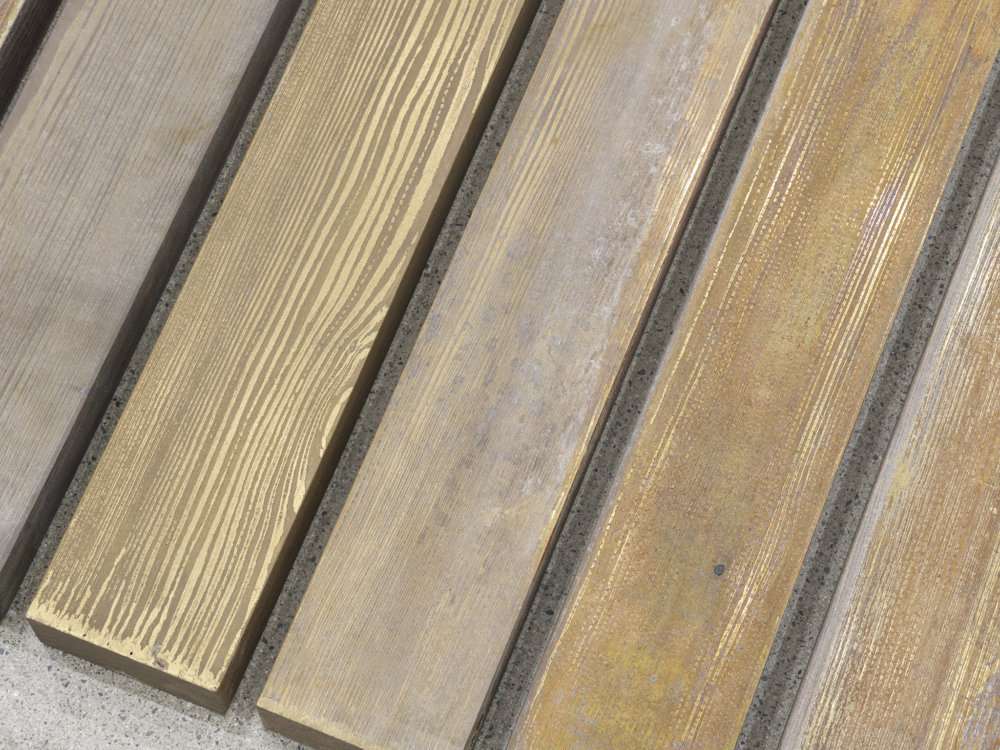

Central to the exhibition is Geoffrey Farmer’s My Genealogy, 2021, an immense acid etched brass sculpture. It exists as a sequenced façade of realistic representations of wood planks, which on first encounter resembles both a minimalist installation and a floating dock. Referring to his own subjective “family tree,” a close relative’s lumber truck accident is the catalyst for both personal and familial distress and for this works formal origins of multiple planks of wood, deriving from a historical photograph of the accident scene. The title and work also refer to the use of the term Genealogy in Foucauldian philosophy, a historical technique of questioning commonly assumed philosophical or social beliefs such as “sexuality” or the role of influential power in presumed historical truths. The planks that form the sculpture have their own history as well, clearly bearing their material experience through welds, holes, water stains and a patina of time, articulating only in part their past lives.

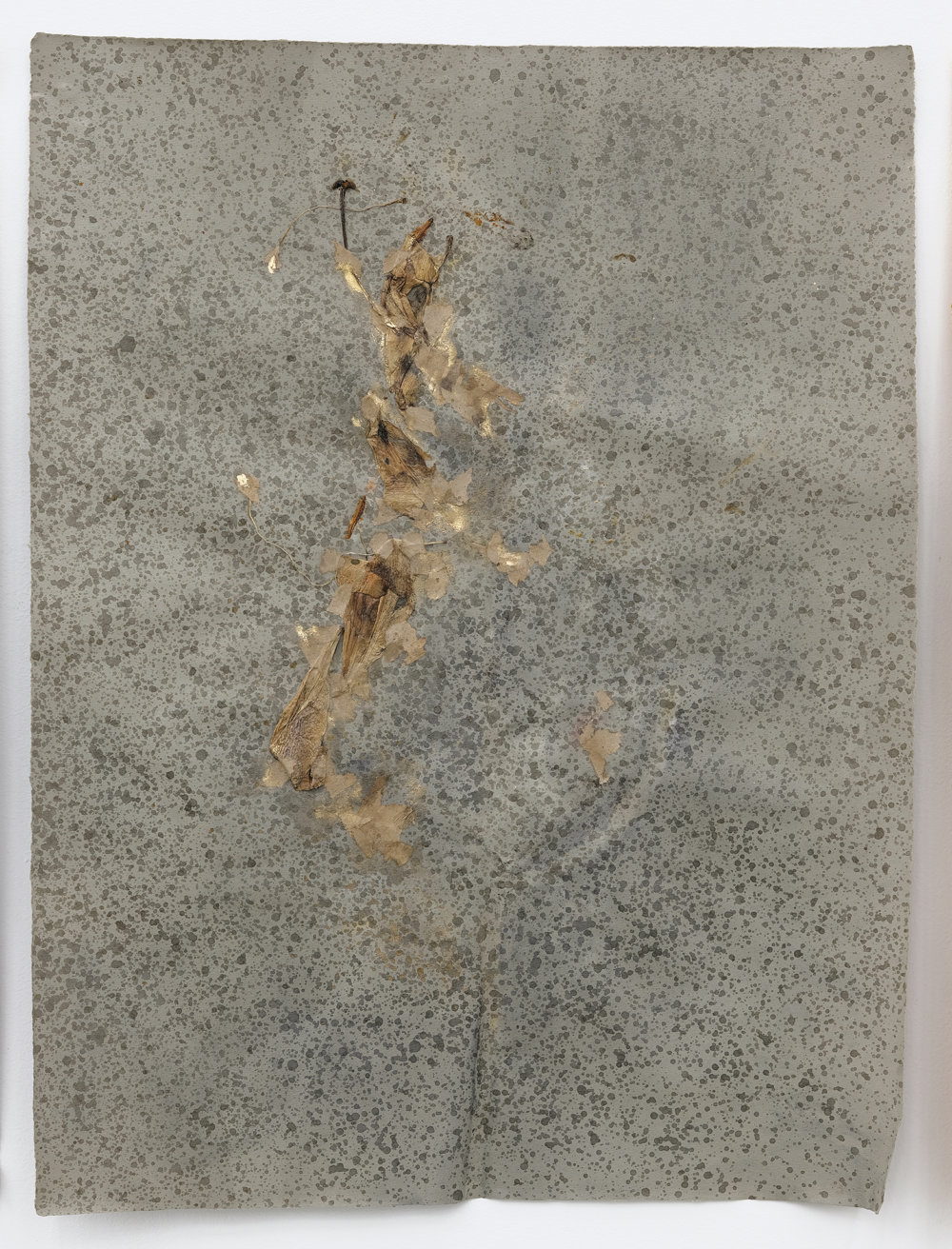

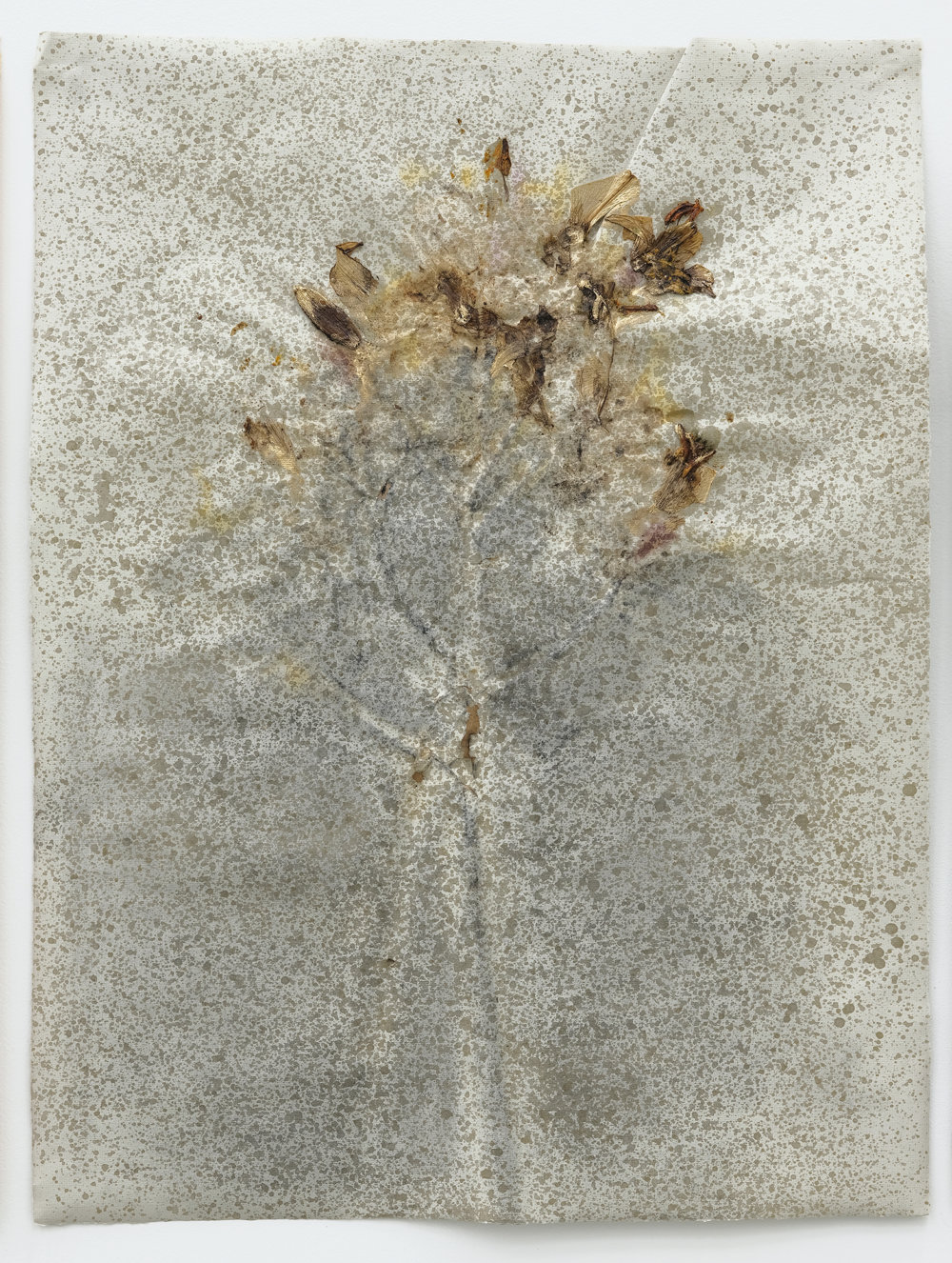

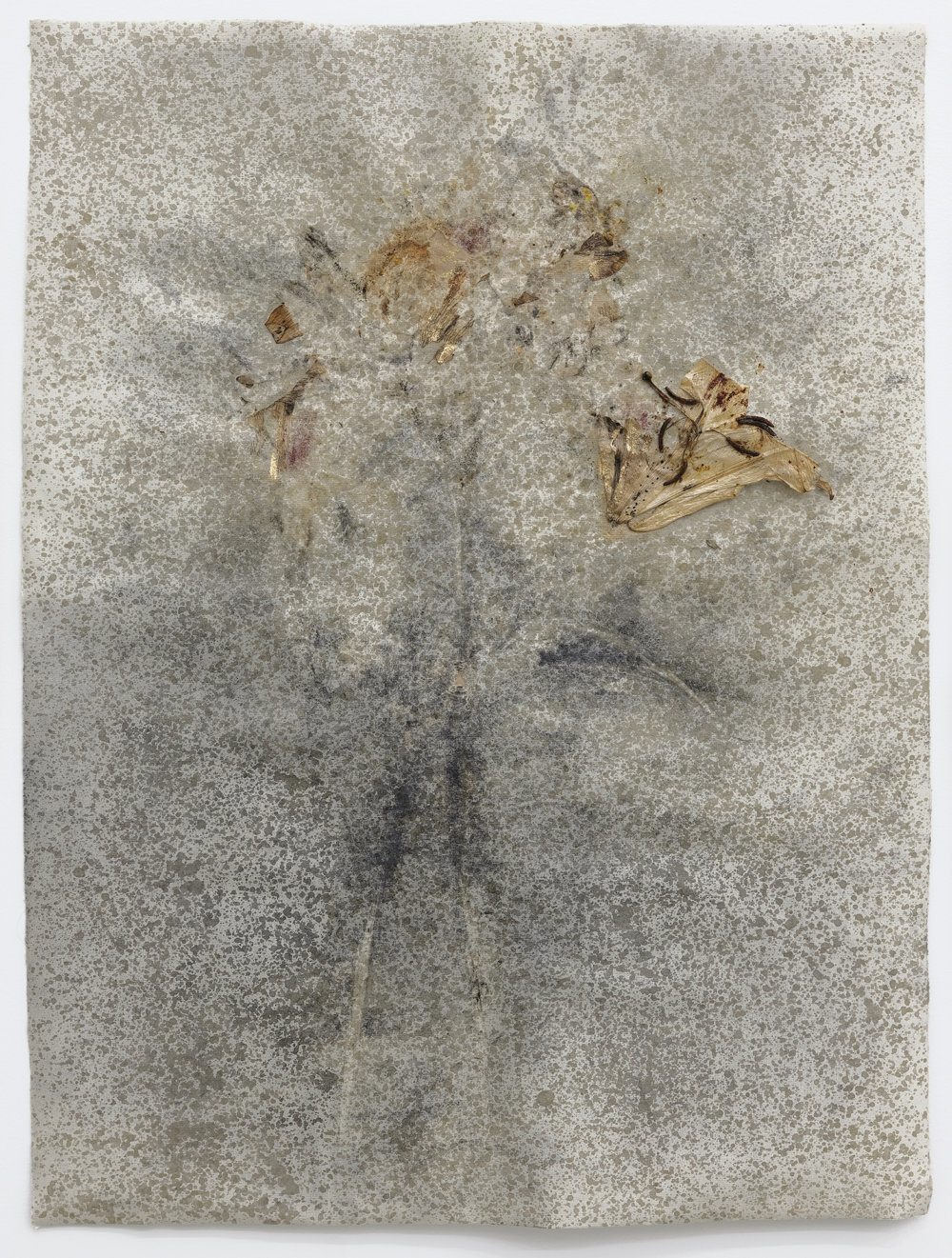

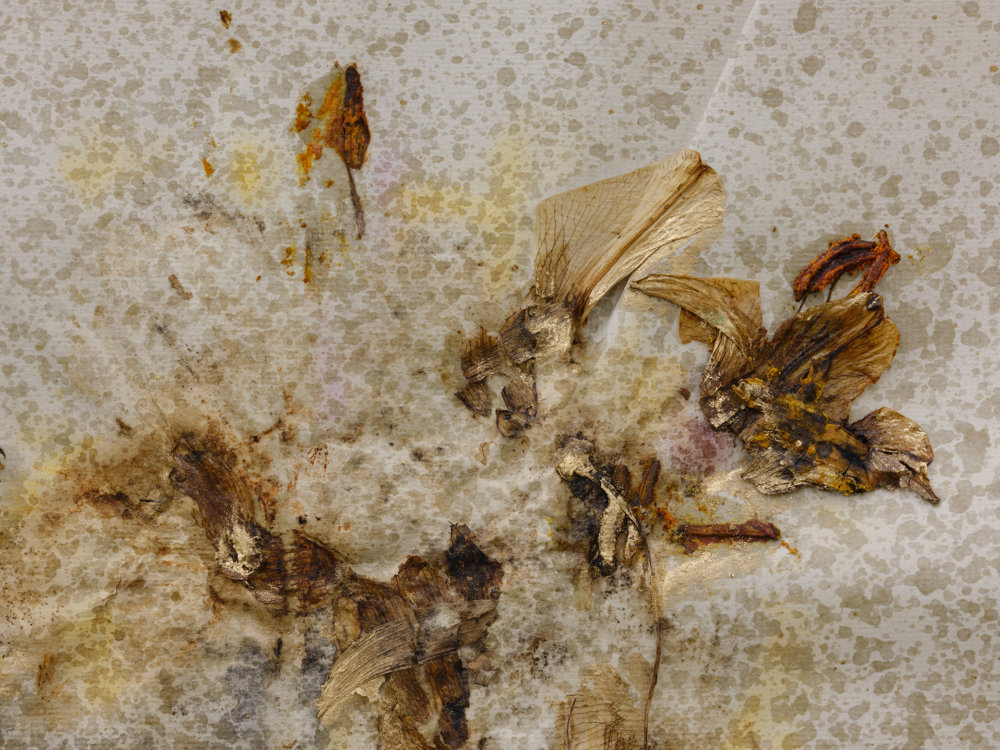

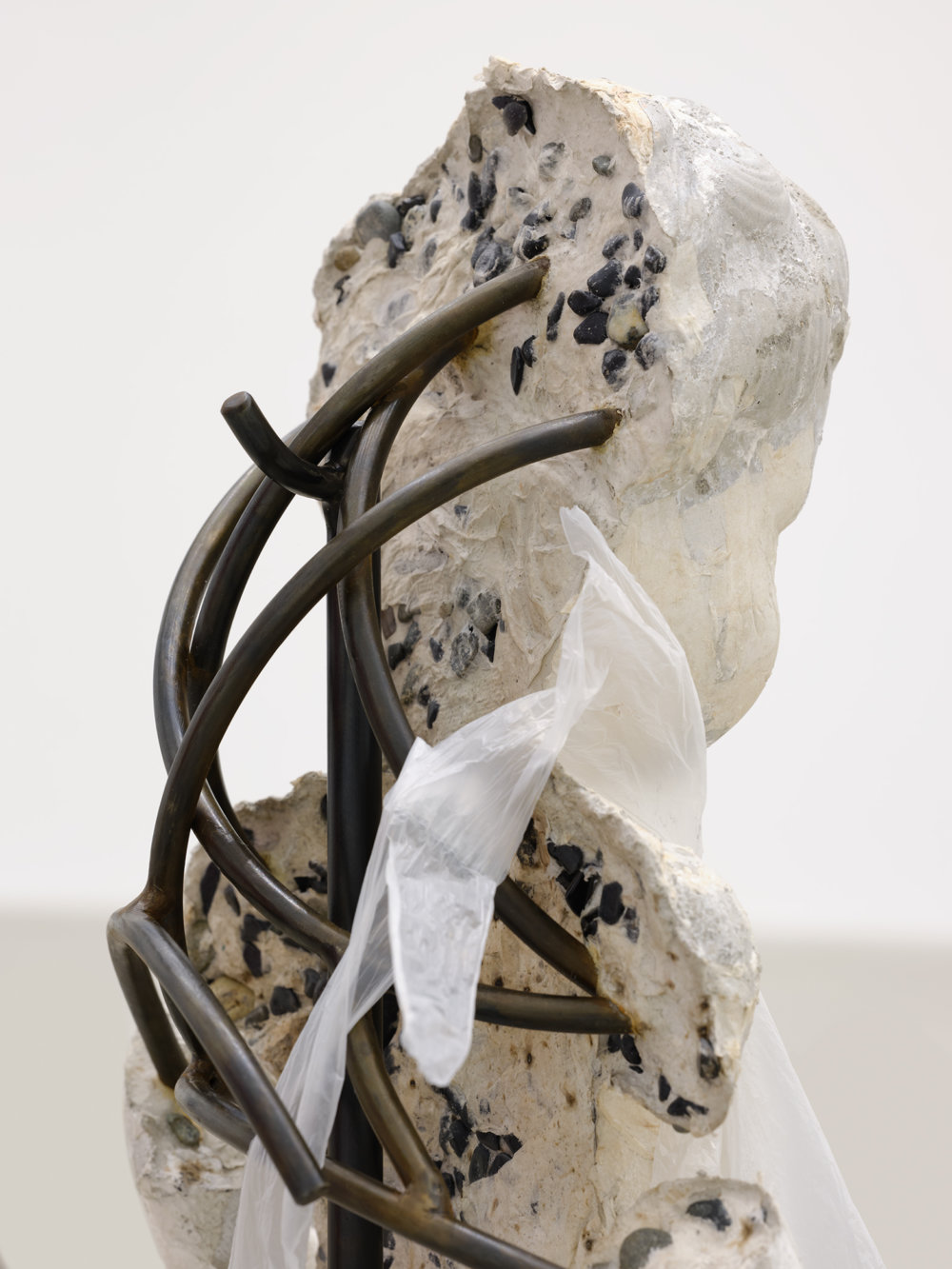

Rochelle Goldberg’s sculpture, installation and wall work continues to ask how we can extrapolate beyond the assumed boundaries between living entities and objects. Goldberg’s notion of ‘intraction’ represents an in-between space, where the boundary between one entity and another is destabilized and where the remains of encounters between multiple material and conceptual realities are articulated. The work here, completed between her studio in Berlin and on site at the gallery, continues to summon historical, ecological, religious and poetic subjects. Deconstructing a bouquet of lily flowers, she interleaved sheets of paper between the plant material as it simultaneously dried and rotted, leaving shadows and plant material itself affixed onto the paper. The work, then treated with shellac and graphite, further articulates this temporal process. Her sculptures, concrete casts of an early commercially available doll, a repeating form in her work, and those of hands grasping rocks in motion confound presumptions of our own knowledge of material processes and symbolic history.

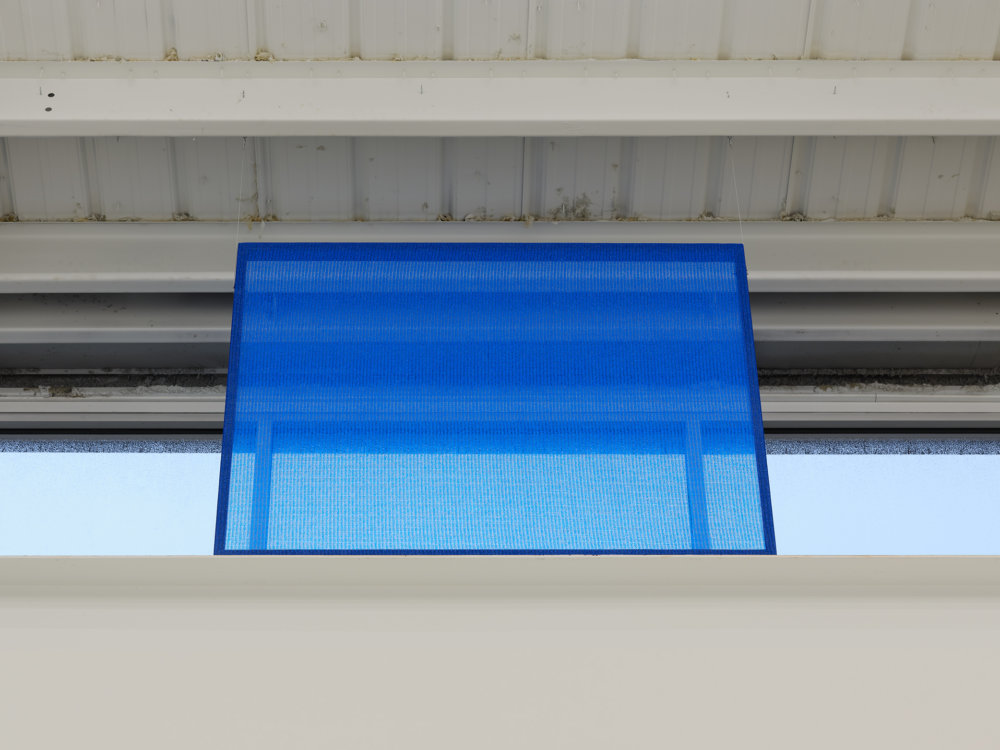

Kapwani Kiwanga’s works speak both to architecture as a controlling device for the human body and to the mediation of vision and knowledge itself. Kiwanga’s practice is formed in research, focusing on forgotten or ignored histories which she translates into in her installations, film, sculpture and videos. While seemingly in direct conversation with minimalist and phenomenological discussions in contemporary art history, these works refuse and complicate an easy reading both through their installation in relation to gallery architecture and through the use of black, white and blue shade cloth. Used globally on plants and fields to control light, temperatures and air flow, this agricultural textile allows non-native plants to be grown in foreign soils and climates, a colonial practice used for centuries. Allowing vision to pass through, but be mediated, these works articulate numerous political and personal underlying filters. A subject’s visibility is not neutral, nor is the viewer or the viewers gaze, all are consistently facilitated by external structures and histories. Despite this, our vision and its potential persists.

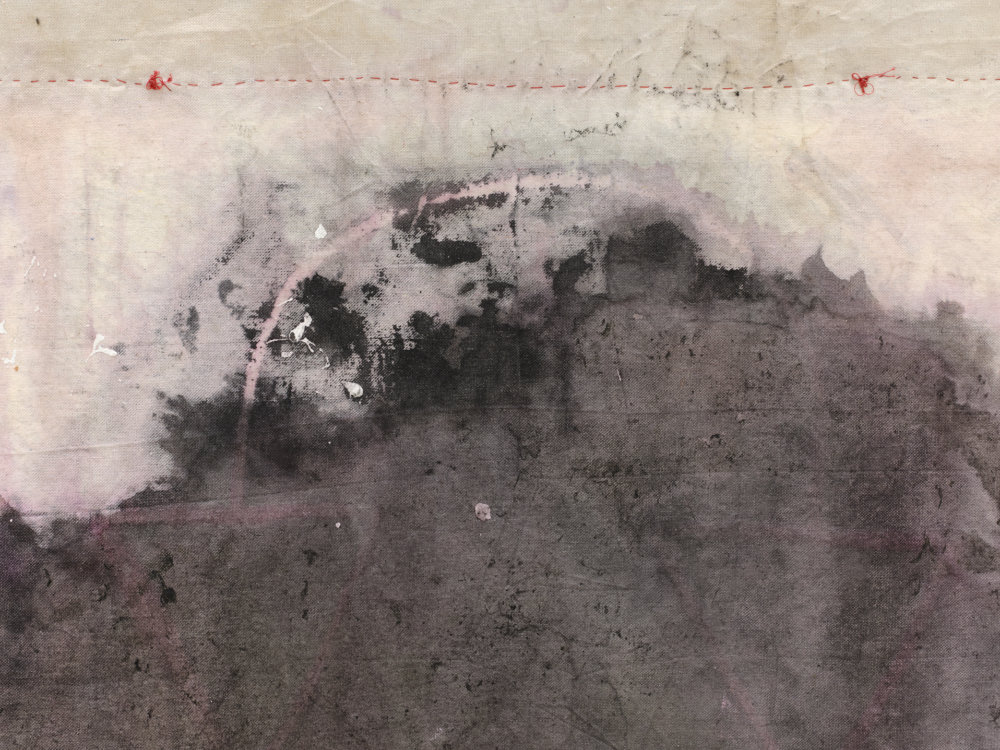

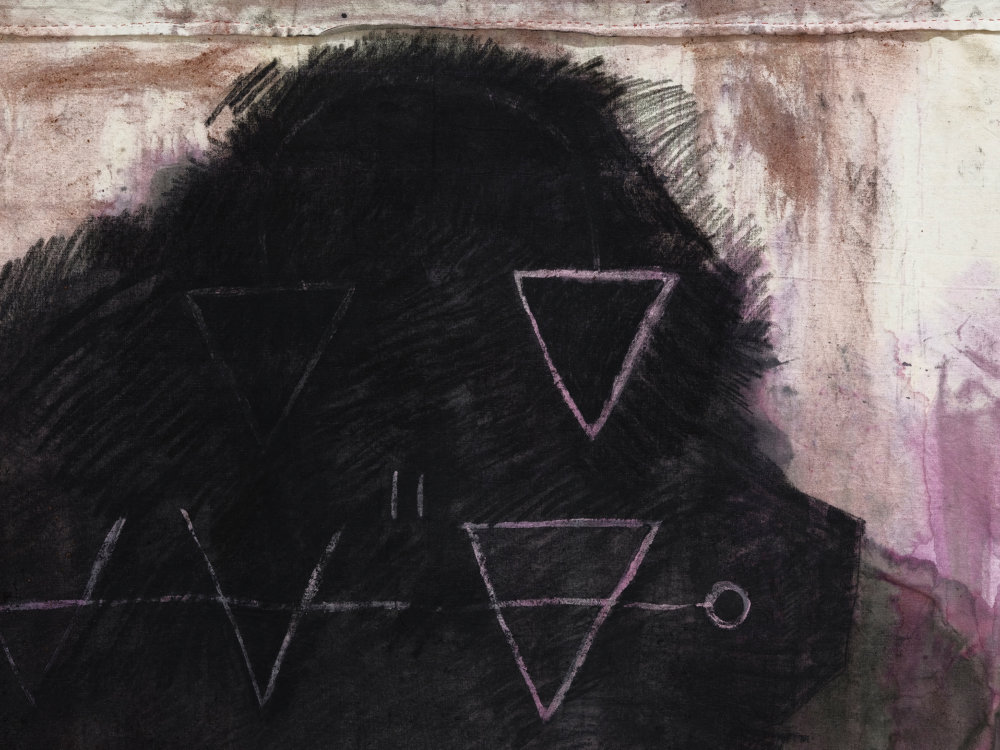

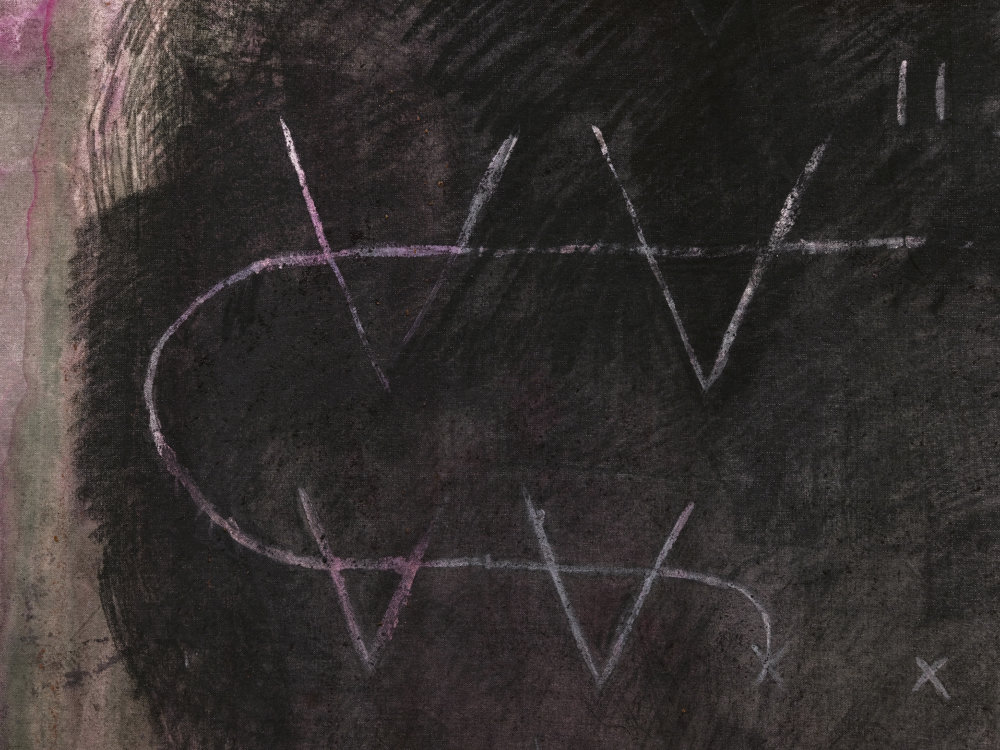

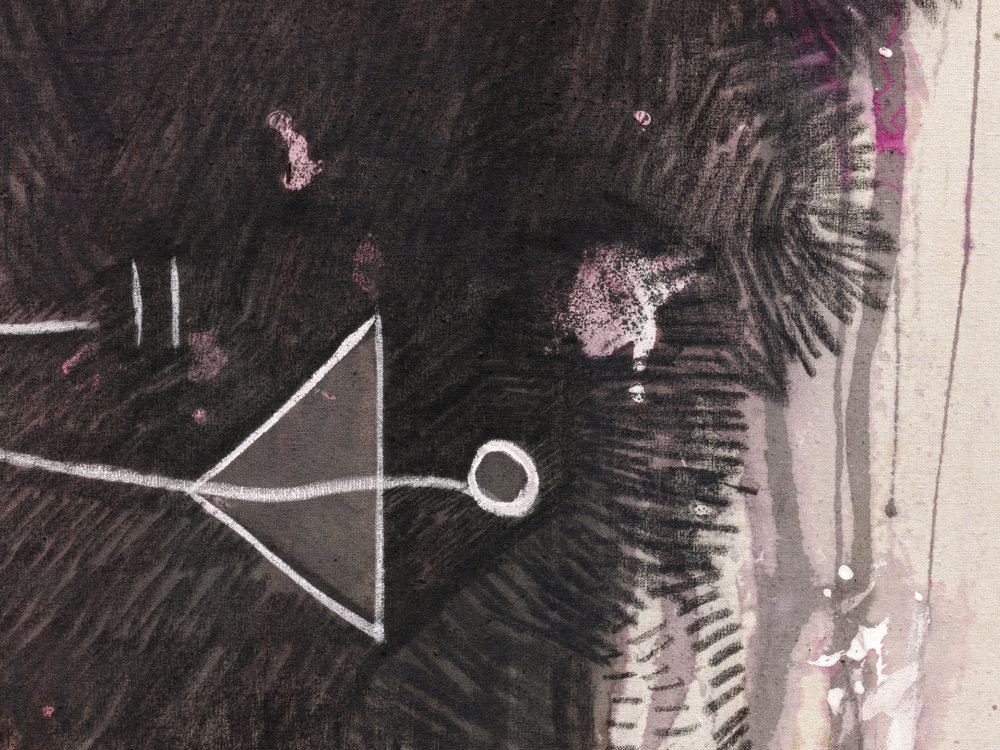

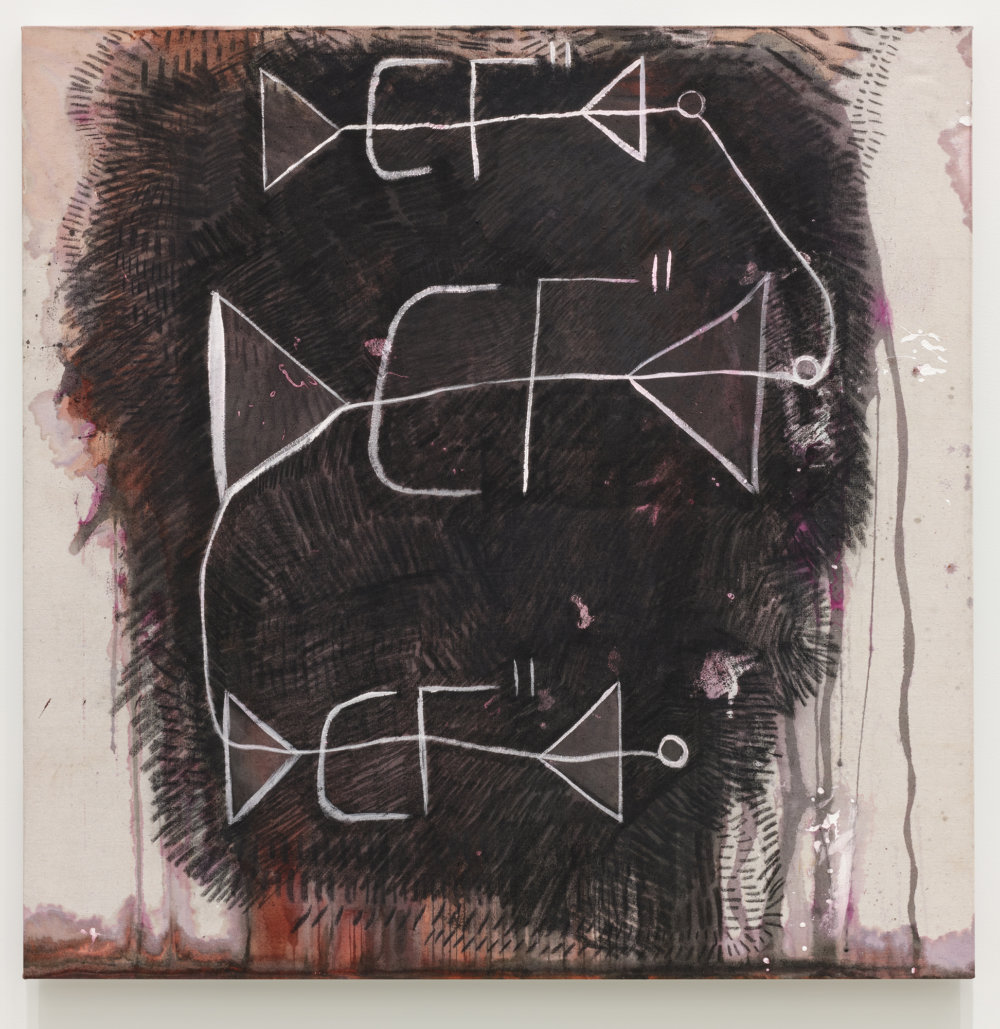

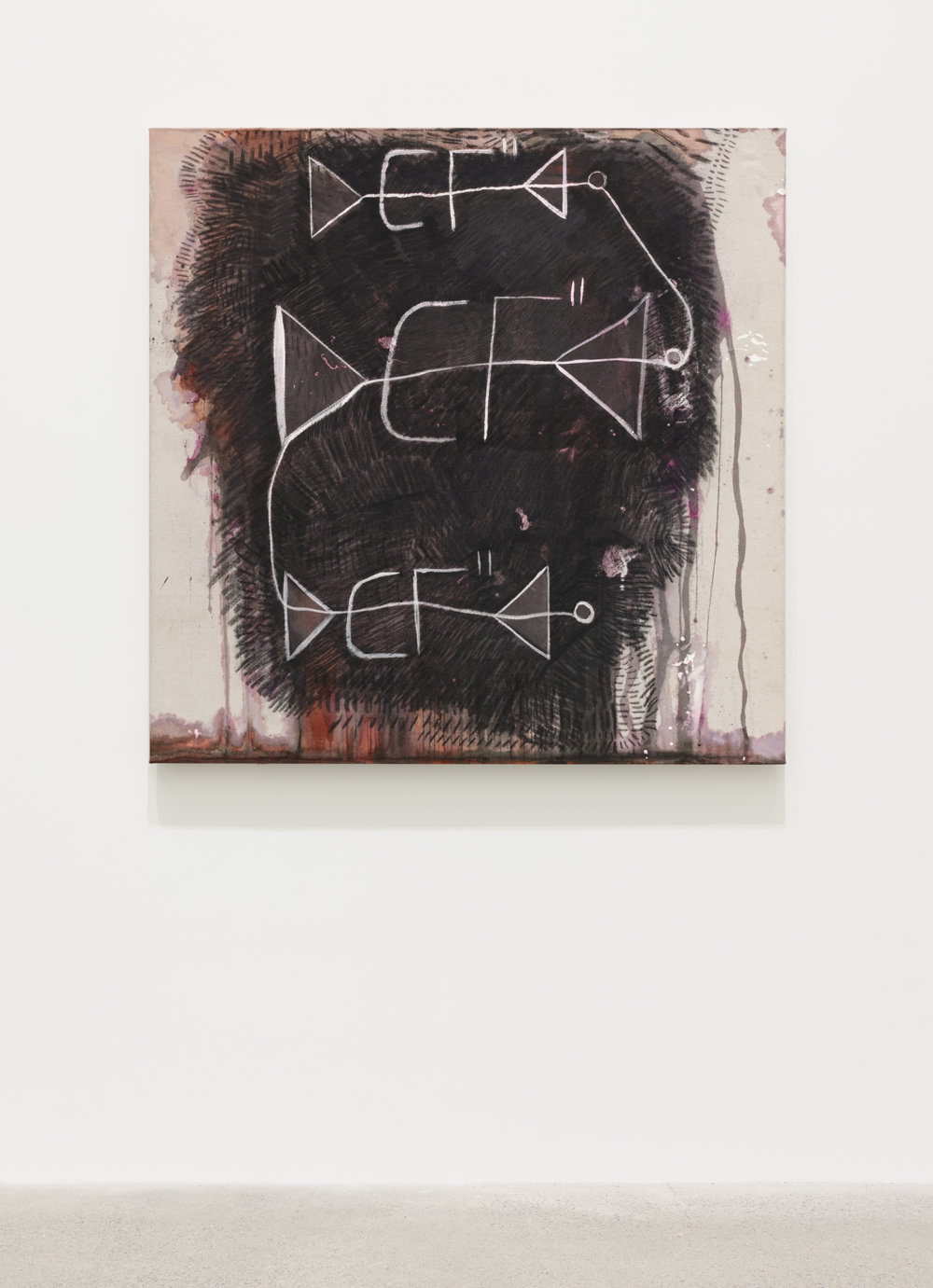

Duane Linklater’s textile works in relation simultaneously articulate and withhold knowledge. The dyed, stained and painted canvases formally engage recent Western abstraction, painting and art history, yet their accrual of traditional Indigenous materials such as sumac, charcoal and cochineal dye, stake claim to another value system and language entirely. Linklater expands on his work with Cree syllabics (a visual Indigenous writing system), drawing them on the surface of the paintings here. The symbols themselves transform into lines suggestive of mapping, the language of formal abstraction or another symbolic communication altogether. The deep, dark areas that provide the ground for these marks can be read simultaneously as shadows of a figurative head in portraiture, as nonfigurative experiment or the result of a process whose context we do not have access to. It is through these multiple layers of material and cultural translations Linklater addresses knowledge lost and gained.

Documentation by Rachel Topham Photography